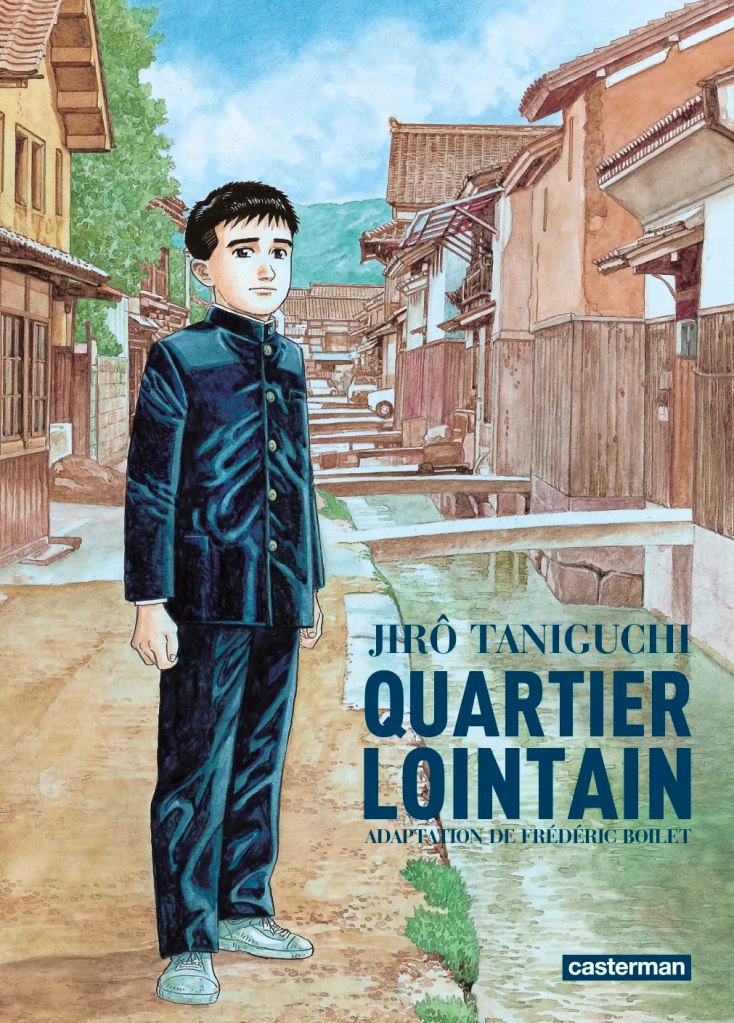

In Quartier lointain, the wonderful manga by Taniguchi Jiro, the hero leaves his family one morning to take the train to work; he falls asleep in the compartment. When he wakes up, he doesn’t recognise the place where he has arrived, and ends up realising that he has returned to his own past when he was ten years old.

I had this feeling when I arrived in Japan for the first time in 2018. The language was totally unknown to me, but not the atmosphere, not the attitude of the Japanese, not the smell of the streets and the sound of the wind, not the light that illuminated Akasaka. I had the feeling that I’d come back home a long time later.

When I returned that year, the friend to whom I had lent my flat during my trip gave me Quartier lointain, which I discovered and devoured. The story had come full circle.

During this trip, I didn’t discover much new, if anything at all. Instead, I went back to see the people and places I loved during my first four trips. It’s a feeling I can hardly share, even in writing, because it’s so powerful. It’s more than an emotion—it’s an overwhelming flood of the senses that overturns my perspectives and radically alters my personality.

I’m not the same person in Japan. I become someone from another life, someone I don’t know very well and discover anew with every step and every encounter. I no longer have an age, a name, or a country. I am simply what the moment offers, with no fear and no limits to my desire to learn and discover. I don’t think, I don’t measure; I am the moment and the movement.

Perhaps that’s why I write this chronicle: to stay connected to my former life and the people I love. I’m a Major Tom speaking to Earth, saying: “I’m stepping through the door and I’m floating in a most peculiar way and the stars look very different today”.

This morning, a Chinese friend living in Japan wrote to me: “The most important thing is to learn to love yourself.”

She’s right. It’s the best way to love others and to love life. It’s not about being a Narcissus, lost in self-admiration to the point of disconnecting from reality. It’s about accepting yourself as you are and drawing the finest honey, the richest nectar, from it.

Japan has given me that. I’ve started to appreciate the old me by discovering the new me, who somehow feels older, as if he comes from a previous life—at least according to my Japanese friends, whose thoughts are deeply influenced by Buddhism and Shintoism.

There are signs, clear traces of my past life, here in Kanazawa, where I’m writing these words from a hospital bed. Even in this place where I’m immobilized, even with a Japanese roommate who snores incessantly day and night, waking only to eat with nauseating noises of slurping and gulping or to call the nurses, speaking loudly no matter the hour—even under these conditions of weakness and helplessness, where I understand very little of what’s being said, Japan calms me.

When I was walking through the streets of Kanazawa before breaking my foot, strangers would thank me—it happened several times. They’d pass me, follow me with their gaze, and then smile warmly and say “Thank you” in English, giving a thumbs-up. Thank you for coming back, thank you for being here—I don’t know. It’s moving beyond words. Have you ever had strangers thank you for no reason?

Sometimes it’s young girls who smile, wave, and giggle as they walk away, whispering to each other. These moments only happen here because this is where I feel at home. And despite my height, my skin, and my gaijin eyes, everyone seems to understand that I’ve lived here—long ago, perhaps very long ago.

In that other life, where I might have been Japanese, did I meet geishas, know samurai, act in kabuki, farm rice fields, or live as a poor merchant, the most despised class during the Edo period? It’s impossible to say. But there is one place where this feeling of déjà vu is strongest: the Daitoku-ji in Kyoto, a cluster of Zen temples. One temple in particular speaks to me. It’s tiny and simple, but every time I sit on its wooden steps and gaze at the raked stone garden, I never want to leave.

I’m in Kanazawa, and the memories are just as vivid here, especially in the 花街 district called 主計町茶屋.

花街

Kagai or Hanamachi – city of flowers, the name given to the pleasure districts.主計町茶屋

Kazuemachi chaya – tea house district.

This is not the best-known of the two districts in Kanazawa. On the other side of the Asano River is the famous ひがし茶屋 where crowds of tourists flock to buy gold-decorated ice cream or visit a teahouse in the hope of catching a glimpse of a Geisha.

ひがし茶屋

Higashi chaya – eastern tea houses.

It is in these two districts that my memory lingers today. Along the teahouses where Geishas used to gather in great numbers and where some of them still do today. On Kanazawa’s famous wooden bridge, which links the two banks of the Asano and was used by the Geishas to cross from one district to another. In the narrow streets where you pass many young women dressed in kimonos. They are not Geishas, of course, but tourists, often Japanese, who relive that era for a day and are often delighted to be noticed, looked at and photographed.

Was I a Geisha? Why not, anything’s possible. Geishas were originally men.