Ohayō

August 14, 2025

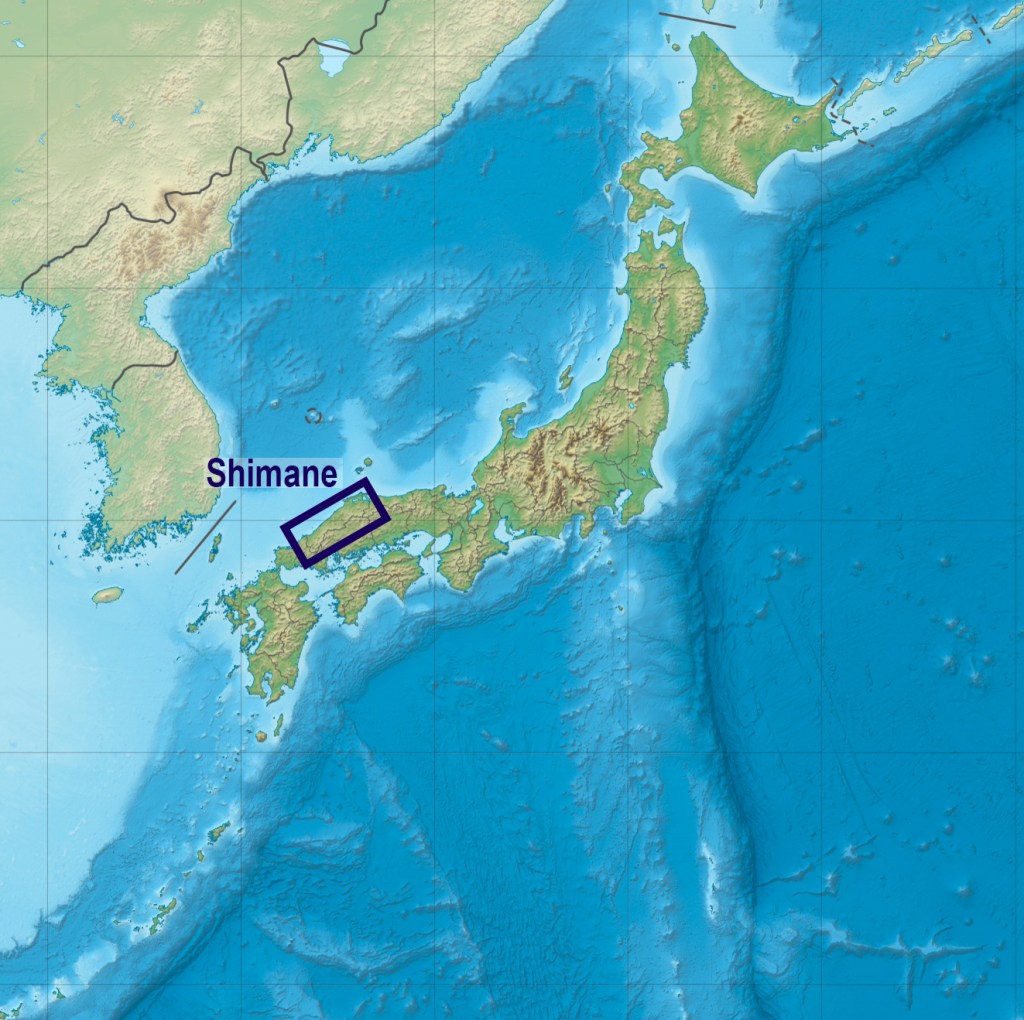

From the train window, the view is spectacular. I leave Honshū to reach Shikoku, crossing the Seto Inland Sea over an immense succession of eleven bridges. They rest on various islands. The whole structure is called 瀬戸大橋; it was completed in 1988, ten years after construction began. It is the largest double-deck bridge in the world, with a road and railway stacked one above the other. It is one of the major symbols of modern Japan.

瀬戸大橋

Seto Ō-hashi — Great Seto Bridge.

Shikoku is often described as the least developed region of Japan; this is not a condescending judgment from the Japanese. Rather, it is to say that this island has preserved an authenticity that is somewhat lacking in the rest of modern Japan, a land where rural life is still very present. This time shift often manifests as a natural warmth towards visitors. A gentle and simple curiosity towards those who cross over and take an interest in this land that is a little wild, sometimes a little rough, but always endearing. It radiates a particular tenderness; it reveals itself little by little, at the pace of one’s steps.

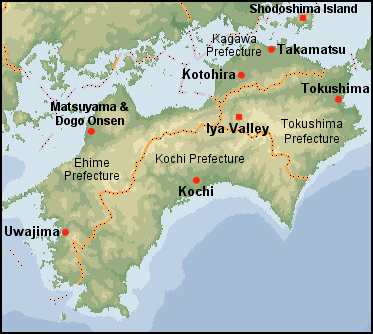

I meet Hisae in Takamatsu, the capital of Kagawa, one of the four prefectures of Shikoku, whose name means “four countries.” She suggests we visit 栗林公園, one of the most beautiful gardens in Japan. At the entrance, a rather elderly man kindly comes to speak with Hisae; she listens attentively. He is talkative and speaks with enthusiasm about the garden, running his hand over the map displayed on large wooden boards. He calmly pulls a bright yellow vest from his bag and puts it on while continuing to talk. He is a volunteer guide: he offers his services to visitors for free, sharing his knowledge, describing the trees, flowers, stones, waterfalls, teahouses, all the remarkable features. He will accompany us for more than two hours.

栗林公園

Ritsurin Kōen — Ritsurin Public Garden.

The garden covers 75 hectares; it backs onto Mount Shiun, a magnificent natural backdrop. The southern part is the oldest; it is in the Edo style and was initiated in 1625 by the daimyō Ikoma Takatoshi. It would then serve as a residence for over two hundred years for the Matsudaira clan, to whom Takamatsu had been given by the shōgun Tokugawa; logically, it is the same clan. When the Tokugawa shogunate was overthrown in 1868, the garden was handed over to the Meiji government, which opened it to the public in 1875. The entire northern part of the garden dates from the Meiji era and was designed according to criteria similar to those of a Western botanical garden. Since 1953, Ritsurin Kōen has held the title of 特別名勝.

特別名勝

Tokubetsu Meishō — special place of scenic beauty.

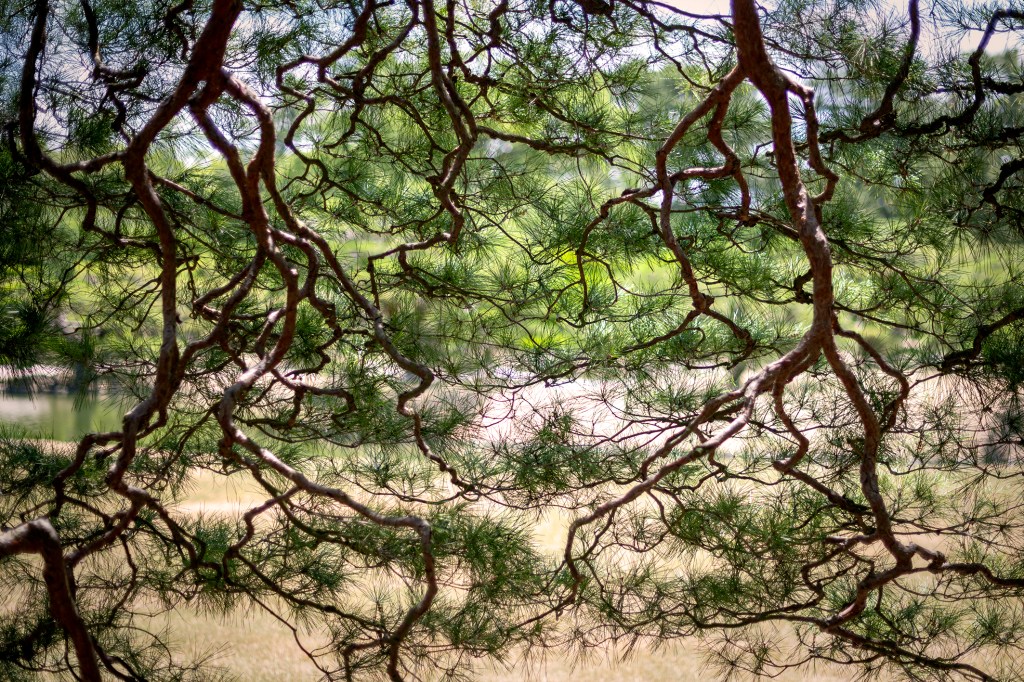

What makes Ritsurin unique, what gives it its beauty and attracts the Japanese, are the pines. There are more than 1,400 of them, many of them over a hundred years old, and a good thousand are regularly pruned by hand, sometimes shaped to grow in a certain way. A traditional pruning technique in Japanese gardens. In Japanese tradition, 松 are a symbol of strength for the samurai. They are found in the gardens of all preserved samurai houses and very often in more modern private gardens. The most famous pine in the park is the 根上り五葉松: originally a bonsai offered to the local lord, it was replanted in open ground around 1830; since then, it has grown freely. This pine is several centuries old and of striking beauty. Its current immensity still retains the form of the bonsai it once was.

松

Matsu — pine.根上り五葉松

Neagari Goyōmatsu — five-needle pine with aerial roots.

Three species of pines are found in the park: 黒松 (kuromatsu), 赤松 (akamatsu), and 五葉松 (goyōmatsu). Some are shaped like cranes or turtles; others have fused into a single trunk; still others form strange galleries shaped by the gardeners. In a Japanese garden, the hand of man is everywhere, yet it must not be seen, which radically distinguishes it from Western gardens. The beauty of nature is enhanced by the gardeners; they withdraw, hide, and vanish, simply letting the symmetrical asymmetry of life express itself. The gardener acts as a revealer rather than a creator; he does not invent, he knows the techniques, the cuts, the pruning, the orientations, and allows the art to exist.

黒松

Kuromatsu — Japanese black pine.赤松

Akamatsu — Japanese red pine.五葉松

Goyōmatsu — Japanese white pine with five needles.

In the northern part, there are carpets of water lilies. They sway on the water, pushed by the wind, still open sometimes when the sun is high. There are forests of lotus emerging from the mud. They spread their majestic circular leaves and allow a few flowers to rise in summer. A symbol of Buddhist awakening, the lotus flower is born from black, sticky water, grows in a uniform canopy, emerges, and blooms in all its beauty, under the sun precisely. Once awakened, its long petals let themselves be caressed by the playful wind, initiating a dance of veils. The heart hides and reveals itself to the rhythm of the warm breath; it plays, it lives, so do I.

Around the six ponds that punctuate the park with shifting reflections, thirteen artificial hills have been created, offering changing viewpoints. One of them, called Mount Fuji, offers what is considered the most beautiful view. It overlooks the pond on which Edo-period boats sail. Steered by a boatman wearing a pointed straw hat, they glide gently, followed by multicolored koïs. They hope for some morsel, upon which they pounce with tumultuous voracity when a passenger lazily tosses it. Koï food is sold at derisory prices and is the only kind allowed. The pellets are made from ingredients carefully selected for the fish’s well-being: algae, vitamins, grains, soy, minerals. One does not joke about the diet of future dragons!

From the top of Mount Fuji Hill, I see the gracefully arched bridge. Completed by its symmetrical reflection, it looks like an eye with eyelashes outlined in black. One can almost make out the head and body of a pine dragon, cleverly integrated into the setting with sophisticated camouflage. It waits for its moment in perfect mimicry with nature. The pond is made of its tears and shelters its koï brothers and sisters. They have not yet reached its status, which makes it a little sad. In its solitude, it knows the effort required for admiring gods to grant such power. The land before it is its impressive jaw, stretching away under the trees. The distant hills form its serpentine body, coiled in a sleeping posture. One of its paws is before me, made of equal pines laid on the ground; the three toes on the left are clearly visible. At night, the eye disappears, closes, the tranquil body breathes softly like an evening breeze. The cicadas fall silent, the koïs drift between two waters. The dragon sleeps, the night is beautiful.

掬月亭 is a teahouse of great beauty. Its origin dates back to 1640; it is located on the edge of the southern pond, opposite Mount Fuji Hill. Even if it is no longer as vast today, its position at the water’s edge makes it a remarkable spot. Open to the pond, I drink suspended matcha tea while a cormorant dries its wings, a lazy boat glides slowly. Its stillness is potential, in harmony with the slow rustle of wind over water. It lays an indigo blue cloth over the dragon’s skin, which sometimes seems to shiver, tickled by the tiny foam flowing along the flat bottom. Or perhaps it is the long pole slowly dipping into the water that comes to gently tease the rough skin between the ribs. Never leaving again becomes an option, unfounded perhaps, but a dream has no time limit.

掬月亭

Kigetsu-tei — teahouse where one scoops up the moon.

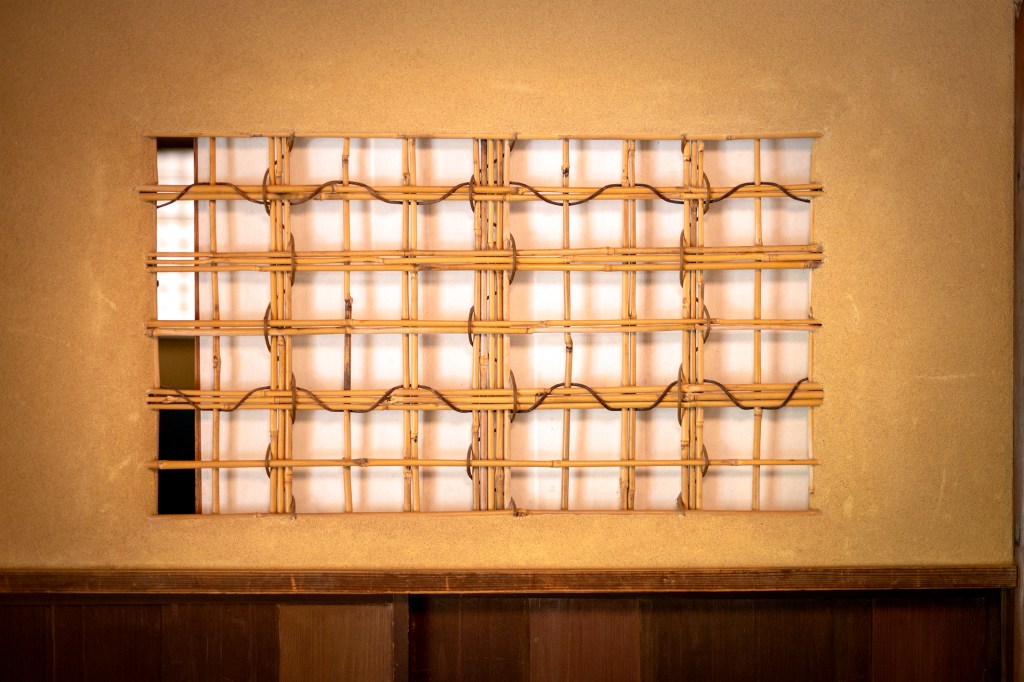

When the sun slowly sinks behind the hills, the teahouse closes like a flower for the night. Its petals are 128 wooden panels, hidden somewhere during the day. They are slid into wooden rails by women in sumptuous kimonos. It is a spectacle of gliding — that of wood rubbing against wood, that of white tabis sliding across the floor, that of fabrics rustling, opening, and closing. At every corner of the house, whose layout is complex, ingenious wooden pivots allow the panels to turn at right angles. The house clothes itself in scales, darkens, wraps itself in a new mystery. Is it part of the dragon?

I returned to Ritsurin three days later, in the morning, to enjoy a different light, another language of nature under a dry, warm sun. I took the time to look alone, for a long while, with the memory of Hisae translating for me the explanations of our volunteer guide. I found the same places again, but I did not follow the same route, breaking away from the path to follow, the suggested path, so cherished in Japan. Everywhere, in gardens, museums, houses to visit, small panels of wood, cardboard, or even stone, decorated with elegant arrows, indicate the way to go. Is it harmonious? In a way, since it is followed by the great majority of visitors.

There are so many paths, so many possible routes in Ritsurin that it is not difficult to find a side path and double back to change one’s perspective. I discover another teahouse that will be my delight, 日暮亭. Its name is fitting, suggesting that the place is so pleasant one could stay from dawn to dusk. A morning matcha is in order, served hot or cold according to one’s taste. The place is very different from the house with 128 panels. Here, nothing is sumptuous; everything is delicate and discreet, in constant contrast with the green luxuriance of the small garden. A well gradually appears among the thickets when the eye lingers. One must wait to see; slowly, the simplicity of all things grows and becomes an object of attention, sometimes of questioning. The asymmetrical symmetry is there, it is everywhere. The bowl, the tea, a window, the framing of a space between house and garden, the slightly wild branches around the well. Time has stopped. I understand — this is the dragon’s heart. Very slowly it beats its rhythm and propels the green blood of life.

日暮亭

Higurashi-tei — pavilion where one spends the day.

Matcha tea has calming properties, but it also gives energy. This tea, ground very finely, unlike others, is consumed entirely, making it much richer. The dragon’s heart has rested me and given me energy again; I resume my walk amid the symmetrical asymmetries. I carry on all day, the garden keeping me, the dragon seducing me; I see its traces everywhere. The bark of the trees, of the pines, seems like scales; the rocks, like teeth or claws; the water, its breath; the wind, the manifestation of its dreams. Everywhere flows its green blood made of plants and water.

Again, the sun sinks; it is time to go, to leave the green universe. The garden closes peacefully like its water lilies, the cicadas vibrate intensely. The time to be alone with the dragon has come. Thousands of them will still emerge from the ground tonight, from its skin, where they have remained six years in the larval state. The dragon’s warm breath allows them to develop, to dry their freshly opened wings. Tomorrow, the new cicadas will vibrate intensely, thus celebrating their final life cycle, that of reproduction, which will last only a week.

I am thirsty and see a hut where one can drink. Three elderly men are around a table generously garnished with large bottles of beer. I sit near them and order one. They talk to me. We toast, we laugh, we speak of the beauty of the garden. They come from Kōchi, in the south of Shikoku, where I will be in a few days. They are three volunteer guides; they are quenching their thirst and are happy to talk to a foreigner. They love a garden and share that joy with me.

I love this country.

Mata ne.