Ohayou

July 31, 2025

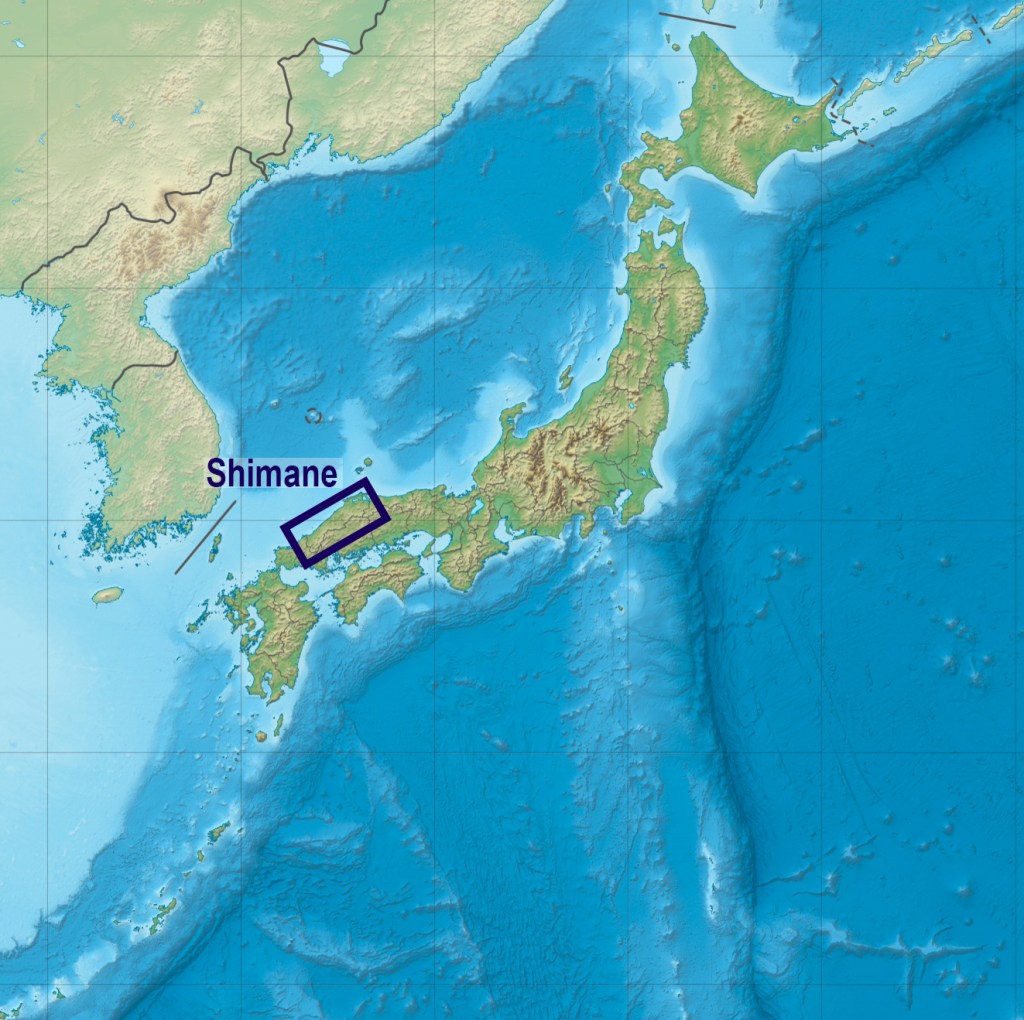

In Shimane Prefecture, which borders Tottori, I went in search of Shinto shrines. I filled my goshuin-chō with red seals, encountered white hares, discovered the most beautiful garden in Japan, met a calligrapher-turned-ceramicist and aesthete of cuisine, admired a painting whose elegant sensuality captivated my gaze, and explored the work of a painter who modernized Japanese painting while preserving its traditional specificity.

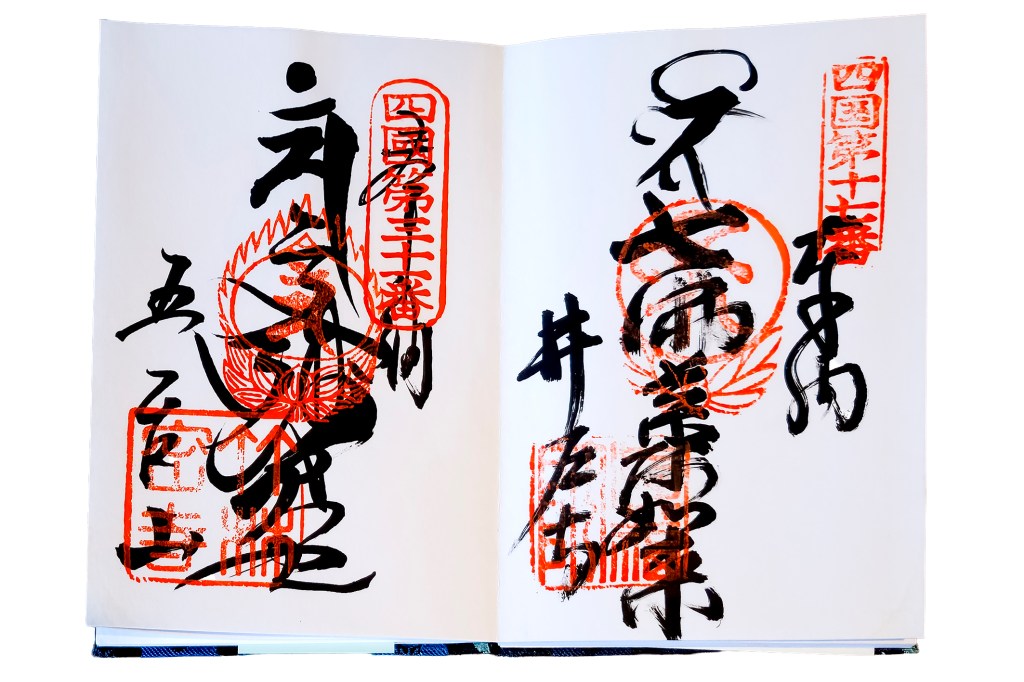

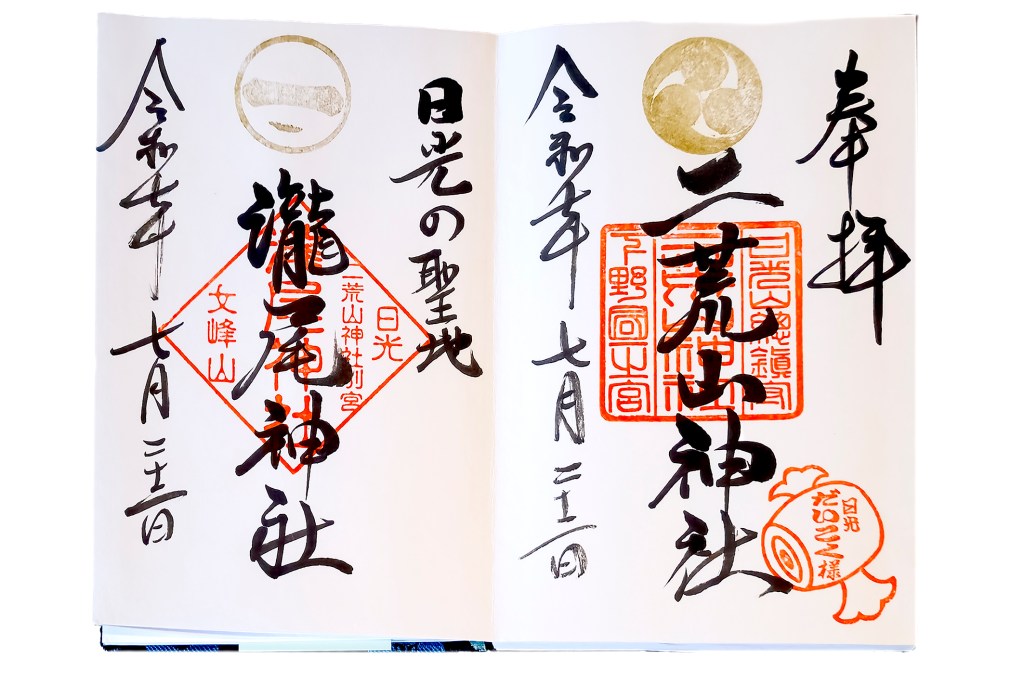

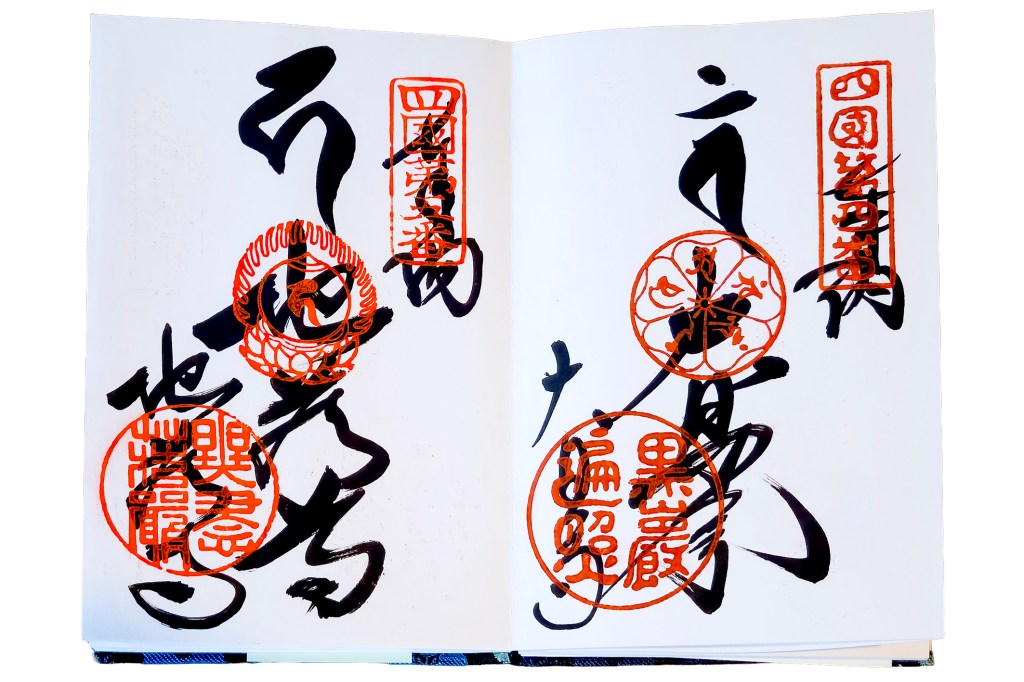

In Japan, travelers carry a 御朱印帳. As they visit Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples, they have red seals, 御朱印, calligraphed into it. For about three euros, Shinto or Buddhist monks, or miko—Shinto priestess assistants dressed in red and white—apply the seals. They calligraph them with grace and elegance, freehand, without resting arm or wrist on the table. Sometimes it’s just dates and place names, other times references to gods in ancient Sanskrit or classical Japanese. It’s not always easy to read, even for Japanese people, but the beauty of the strokes alone delights the eyes.

御朱印帳

Goshuin chō – seal notebook.

御朱印

Goshuin – honorary red seal.

Calligraphers sit in a small wooden booth attached to the temple or shrine. There, one can purchase all kinds of amulets, protective charms, and various symbols tied to the faith or to the Chinese zodiac, which is widespread in Japan. Each sign has a protective deity from Chinese Buddhist tradition, itself rooted in Hindu Buddhism. I am 寅, and my guardian deity is 虚空蔵菩薩, Bodhisattva of wisdom and infinite space. In Buddhism, Bodhisattvas (Bosatsu in Japanese), literally “beings of awakening” in ancient Sanskrit, are beings who renounced entering Nirvana—the place of total liberation—in order to help humans free themselves from suffering. The Bodhisattvas have made four great vows: to save all sentient beings; to eliminate all passions; to master all teachings; to attain perfect enlightenment.

寅

Tora – tiger.

虚空蔵菩薩

Kokūzō Bosatsu.

Shimane Prefecture has a distinctive geography. Its northern capital, Matsue, is flanked by two large lakes, Shinji and Nakaumi. Above them, peninsulas stretch left and right into the sea. I traveled to the tip of the northeast peninsula to discover Miho Jinja, a Shinto shrine dedicated to Ebisu, god of fishing, prosperity, and merchants, and to Mihotsuhime, an agricultural deity associated with fertility and harvests.

I like to lose myself in such places, visited only by a few vacationing Japanese who come to make a wish or show their children a place of cultural meaning. The heat encourages calm, the sun beats down. Cicadas resonate in waves, seeming to intensify their buzzing as I approach a cluster of trees. I can’t see them, but the sound is so intense it seems to overwhelm everything, even to frighten. Some details catch my eye: a lamp, a demon mask, a pair of sandals, a 狛犬, the shrine guardian, in a posture somewhere between playfulness and aggression.

狛犬

Komainu – lion-dog.

Leaving through the torii marking the entrance, I see to the left a cobbled street lined with wooden houses; it seems from another time. This is Miho no Sando, the shrine road. Legend says that since the 9th century, sailors stopped at the port and took this path to pray to Ebisu. It is also said that the gods themselves walked this road. It is a strange place, dizzyingly calm in contrast to the intensity of the cicadas. Nothing happens, or rather, nothing passes except the teasing brush of a sea god.

Forty kilometers away, the atmosphere changes completely. The immense Izumo Taisha, one of the most important Shinto shrines in Japan, draws a constant crowd. The deity worshiped here is none other than Ebisu’s father, 大国主, one of the rare Shinto gods called “great.” He is so important that every October, all Shinto gods gather at Izumo Taisha. His name means “Great Lord of the Land,” and his task was to consolidate mythical Shinto Japan. His legend is tied to the White Hare of Inaba.

大国主

Ōkuninushi – Great Lord of the Land.

The legend is recorded in 古事記, literally Chronicles of Ancient Events, dating from 712. Along with Nihon Shoki (720), it is one of the two foundational texts of Shinto mythology. Their aim was to explain the creation of Japan by the 神 and justify the emperor’s divine lineage. Ordered by Empress Genmei and written by Ō no Yasumaro based on Hieda no Are’s tales, it is considered the oldest surviving Japanese text.

古事記

Kojiki – Chronicles of Ancient Events.

神

Kami – Shinto deity.

Ōkuninushi was the youngest of eighty brothers, who were mocking and cruel, while he was kind and compassionate. They despised him, treating him like a servant despite his divine nature. On a journey to court a beautiful princess from a neighboring land, the brothers encountered a white hare whose fur had been stripped by an angry crocodile after the hare mocked him. The brothers’ cruelty showed: they told the hare to bathe in the sea and dry in the sun. Then came Ōkuninushi, carrying their bags, who saw the hare writhing in pain. Pitying him, he advised the hare to wash in a river and roll in sedge pollen. The treatment restored the white fur. In gratitude, the hare predicted Ōkuninushi would marry the princess. He did, to the great anger of his brothers.

That is why white hares abound within Izumo Taisha. The animal is directly tied to Ōkuninushi’s rise to the top of the Shinto pantheon, which comprises an incalculable number of deities. The contrast is striking between the animal and the majesty of the buildings, which command respect and, through their grandeur and beauty, signify the site’s importance. Surrounding the main structures, inside and out, are tiny, discreet shrines where one makes wishes while gazing at nature, forest, or waterfall.

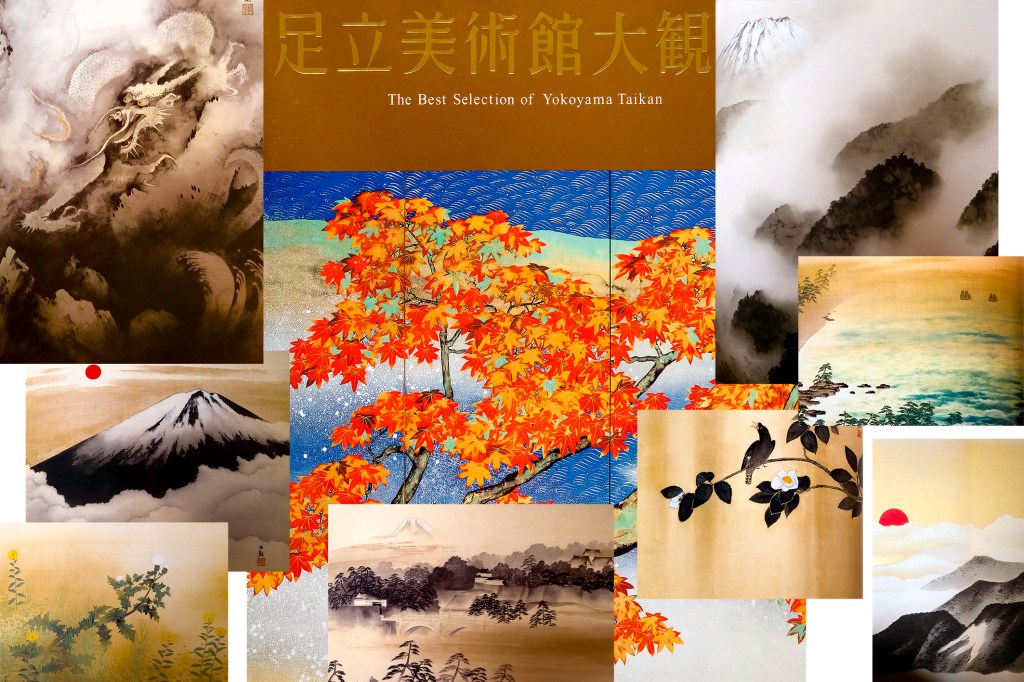

On the road to Matsue, Shimane’s capital, I stop at the Adachi Museum of Art. My friend Hisae recommended it, and her advice led to stunning beauty. The artworks are remarkable, and the museum is set in what The Journal of Japanese Gardening calls the most beautiful garden in Japan. Adachi Zenko, the museum’s founder in 1970, wanted “a garden as a painting,” and it is a dazzling success. Windows and openings were specially designed to frame various views of the garden, into which no one steps.

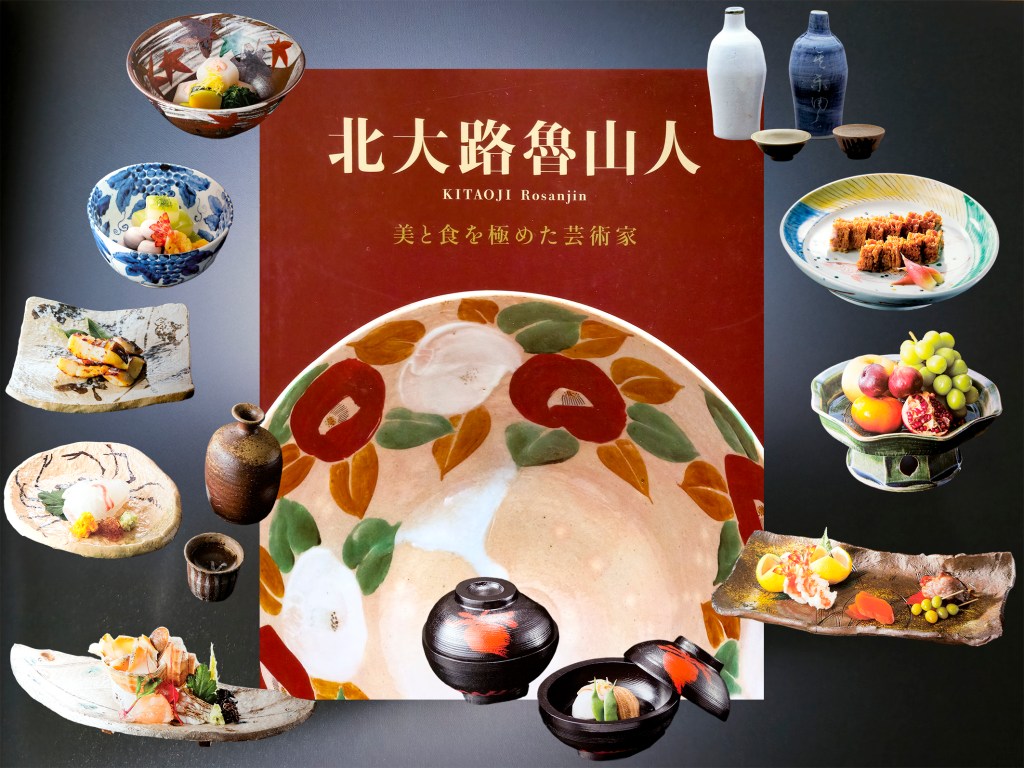

The museum’s first hall, while the garden already captivates, is dedicated to Kitaōji Rosanjin, a unique and surprising artist. Born in 1883 into a noble samurai family, he was abandoned by his mother after his father’s suicide when he was six months old. Taken in by a family of seal engravers, he entered the art world early via calligraphy and Chinese scholarly culture. Rosanjin was self-taught, with an independent spirit and a relentless thirst for knowledge. Without formal schooling, he became a sought-after calligrapher and seal engraver.

He went further, learning pottery and ceramics, where his creative imagination shone. He developed the idea of cuisine where the preparation of dishes is intimately linked to the vessels in which they are served. “A good cook must be a good ceramicist, and vice versa. Taste begins with the eye.” Avant-garde yet advocating a return to traditional Japan, his works provoke, and Picasso himself supposedly said: “He is the only ceramicist who understands the material like a painter.”

Rosanjin’s works are extraordinary, clearly serving his philosophy. Imagine eating from such plates, drinking from such glasses. Picture fine sake shimmering in an elegantly decorated cup, or raw fish, ideally sliced, resting on ceramic art that enhances its beauty. Feel under the chopsticks the delicate relief of an inventive, slightly mad creation that highlights the marbled red and gold of meat. Understand that an eye enchanted by the color and form of a dish where vegetable juice slowly pearls multiplies the pleasure before even tasting.

© Philippe Daman

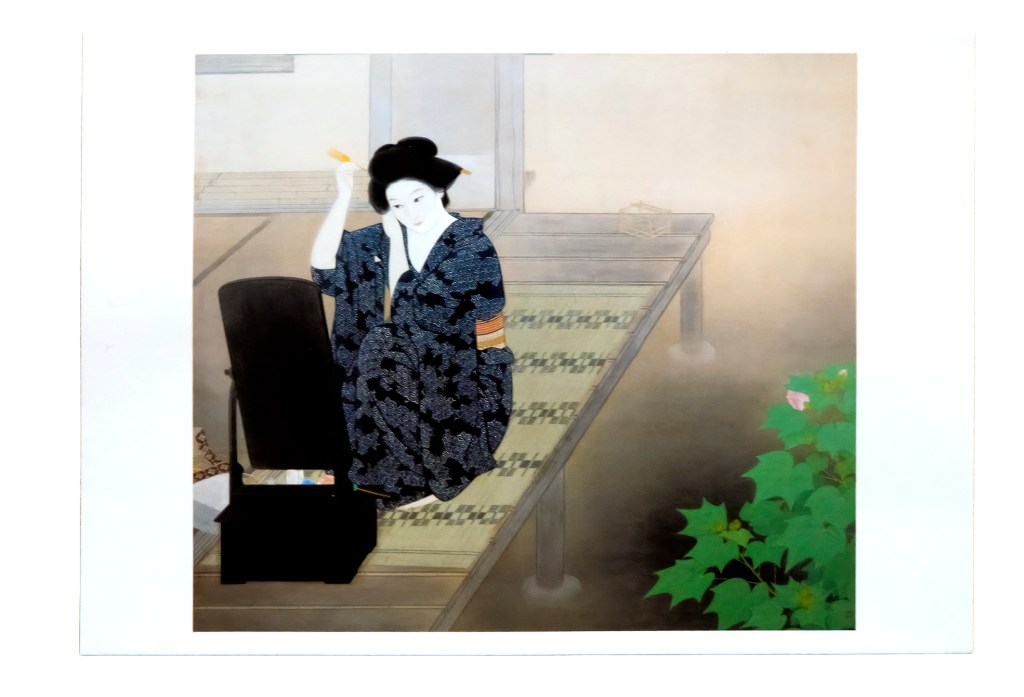

A woman kneels on the wooden veranda of a Japanese house, fixing her hair with 笄. Dressed in kimono, she faces a mirror. Below her, the water of a traditional garden pond can be glimpsed. Behind her, a 虫籠, perhaps containing a cicada or firefly, suggests she is about to go out. The painting is of exquisite grace, the elegance of the gesture balanced by foreground foliage that gives the scene depth.

笄

Kogai – long hairpin.

虫籠

Mushi kago – insect cage.

The work, from a postcard I bought at the Adachi Museum, is by Tetsu Katsuta and titled 夕ベ (1934). Written in katakana, it likely represents a name. Katsuta is not well known, even less so in the West, but his painting represents a Japanese artistic movement from the late 19th century, 日本画. The name may seem trivial, but it reflects a desire to counter the dominance of Western art after Japan’s opening to the modern world. From 1880, painting trended toward Western techniques, forms, and subjects. This movement sought to maintain a traditional Japanese approach while innovating. The Adachi Museum holds an impressive collection of works by its theorist and creator, Yokoyama Taikan (1868–1958).

夕べ

Yuube – evening.日本画

Nihonga – Japanese painting.

© Philippe Daman

In the small teahouse of the Adachi Museum of Art, water is boiled in a pure gold kettle. Such kettles symbolized good fortune and were believed to grant happiness and longevity. Two rectangular windows, like hanging scrolls, offer changing views of Japan’s most beautiful garden. Four women join me for matcha tea. They are from Kyoto, and we share the velvety bitterness of green foam—an emulsion of powdered tea mixed with water using a bamboo whisk, served in an irregular earthenware bowl. The elegance of wabi-sabi meets the softness of our conversation. Everything is simple, beautiful, perfectly harmonious. Time slows gently. Our eyes wander, the cicadas sing, the world is beautiful.

I love this country

Mata ne