Ohayou

July 25, 2025

As the crow flies, Fukui is 180 kilometers from Tottori in the prefecture of the same name. By car, the shortest route is over 300 kilometers; by train, it takes nearly six hours with three different lines. Japan is not always easy when it comes to transportation; it may seem paradoxical in a country where everything appears so well organized. Geography, terrain, or simply the lack of any practical interest in a journey can make a seemingly simple trip quite complicated. It is the dunes of Tottori that compel me to undertake this complicated journey. For a reason I’ve known for a long time, and for another that I will discover by going there.

Long before I first traveled to Japan in 2018, I had developed a genuine fascination with Japanese cinema, which began, I think, when I saw Seven Samurai by Akira Kurosawa at a very young age. It is difficult to see Japanese cinema in Europe: it is ignored outside of certain festivals and film archives, such as those in Paris, Brussels, or Berlin. I consider it the most important and the best cinema in the world today; that is, of course, just my opinion. Its annual output equals that of the United States in terms of number of films and is incomparably better. Thanks to the internet, I was able to discover dozens of directors and hundreds of films completely inaccessible in the West.

Woman in the Dunes, directed in 1964 by Hiroshi Teshigahara, is one of the defining films of this journey. Inspired by the novel by Kōbō Abe published in 1962, who also wrote the screenplay, the film is a meditation on freedom and the absurdity of life. An amateur entomologist, searching for insects that live in the sand, finds himself trapped with a woman in a house at the bottom of a pit in the dunes. He is forced to help the woman constantly remove sand from the house, and despite his attempts to rebel, he gradually loses his identity. This astonishing, unclassifiable film, like the novel that inspired it, takes place in the dunes of Tottori.

砂の女

Suna no onna – woman of the sands.

I had long wanted to see the place where the film was shot more than sixty years ago. To see that almost living sand against which the couple struggles. A sand that insinuates itself, collapses, buries, kills, dries out the eyes, the mucous membranes, the skin, and ultimately the very minds of the characters. To discover whether the sand-filled pits where the houses of that strange and terrifying village stand really exist. The answer is no, of course; desire tricked me once again, and I couldn’t help but feel disappointed, to suffer, when I discovered the extent of the Tottori dunes.

Struggling forward in the sand under a heavy sun, the disappointment faded and all that remained was the memory of the film’s beginning. The entomologist slips with each step on the rolling sand as he climbs the dune; he sweats profusely, short of breath, heart pounding, happy with the effort, to be alone amidst the tiny life that draws him in. So I forget the Chinese tourists photographing themselves to absurdity. I forget the openly sulky young woman; she strikes poses and bursts into fake smiles for her self-portraits. The lie is right there, you just have to look. The mind can wander elsewhere, find in memory the questions raised by a film, by this film. Walking in the sand revives the aesthetic beauty of Teshigahara’s work, the intense emotion of discovering it. The woman of the sands, the woman of the dunes, is there, waiting for me, thanking me for coming.

In dunes of sand with high crests, it is easy to find oneself alone, to feel a little afraid. The sand we played with as innocent and unaware children becomes a monster that swallows its prey when it turns dangerous. That tiny half-millimeter rock is polished over time, by friction and erosion. Though it may seem solid when it absorbs moisture, like our childhood sandcastles once were, it really only wants to roll, crumble, and collapse for our great delight under the assault of tidal waves. Dry, it can run through our fingers, cover part of the body we bury to create optical illusions, or become that muddy paste saturated with water we used to throw at each other, crying with laughter.

On the nearly deserted beaches of Japan, in the unique dunes of Tottori, I saw no sandcastles built by children, but I found them in an impermanent museum that showcases impressive creations by artists from around the world. The 砂の美術館 was created in 2006, initially with outdoor exhibitions in the dunes themselves, before hosting works indoors from 2014 onward to preserve them longer, up to nine months. This year’s theme is Japan, to celebrate at the same time the Osaka World Expo. The works are up to 20 meters wide and ten meters high; they are made from several tons of sand. They depict scenes from Japanese history using only dune sand and water.

砂の美術館

Suna no bijutsukan – sand museum.

The small town of Kurayoshi, where I arrive the next day, is overwhelmed by a scorching sun. It is barely ten in the morning, yet the streets are almost empty. Only cars move about, and it’s not uncommon to see someone idling, engine running, dozing behind the wheel while the motor hums to power the air conditioning. What are they doing? Waiting for someone? Cooling off before braving the sun? Some doze off, others have their legs up on the dashboard in a clearly assumed nap posture; some use electronics to pass the time: games, manga, social media.

I am the only one walking under the sun, the only madman perhaps, from a Japanese point of view. When I accidentally cross paths with a local lost in the harsh and dry heat, he or she is in a hurry, eager to be elsewhere, anywhere but in the sun. A few bicycles pass, overtake or cross me. They are ridden by samurai with impressive gear: visored helmets with 20-30 centimeter extensions that likely block their view of the road; black or white arm sleeves covering their arms completely; matching gloves with a few fingers shyly poking out; shin guards under shorts or skirts; high socks plunged into sandals that alone suggest a desire for coolness. Directly under the sun, not a patch of skin can be seen. How do they not suffocate under all that?

I climb a hill under the trees, Mount Utsubuki; the path, a bit steep and rough, leads to the ruins of Kurayoshi Castle, built by the Yamana clan when they ruled this region and others in the second half of the 14th century. Nothing remains; scattered stones lie along the path with no way to guess or even imagine a structure. Imagination is needed to see a castle, and I am the only one on this hill sweating and hoping to see it. Sometimes, a path taken at random leads only to a dead end; this reminds us that in travel, it’s not the destination that matters, but the journey. It becomes one of Japan’s harmonious ways.

Looking for a more comfortable spot to quench my thirst, I’m surprised to find an unexpected sign in this slightly lost area: Brew Lab Kurayoshi. A countryside microbrewery—how surprising and charming. The welcome is enthusiastic to say the least. A couple bustles behind a wooden bar with six taps. A large window opens onto gleaming vats. They work the hops under the watchful eye of a bearded Japanese giant. He moves from vat to vat, checks pressure, monitors temperature, ensures the product is good. And it is. The craft beer brewed by this microbrewery is remarkable, balanced, flavorful; it slides down, to quote Jean-Pierre Marielle in Calmos.

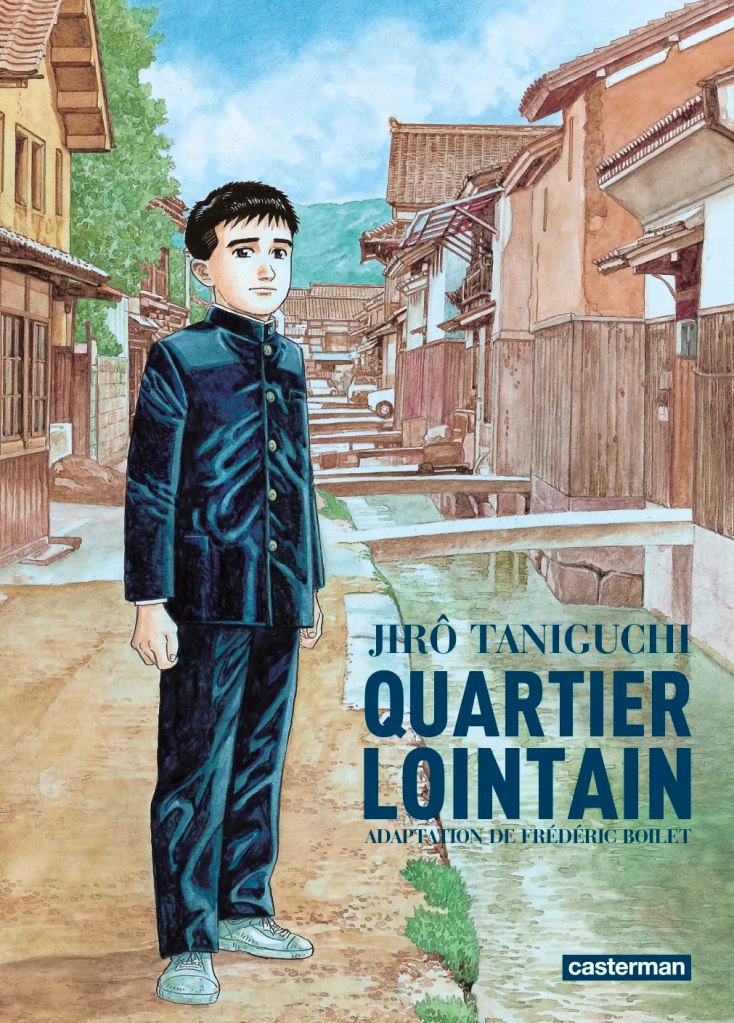

The conversation also slides, natural, obvious. Where are you from, what do you do, why Japan? It could be superficial—it’s not: there is immediately a mutual sincerity that hints at something stronger, unexpected, surprising. The house that hosts the microbrewery is a hundred years old, it’s beautiful, and its structure draws me in. I’m invited to visit, to walk through the garden, to look at this little piece of Japan that reminds me of something… but what? When I return, there’s a manga on the bar. I recognize it instantly, I’ve mentioned it in an article; it was given to me by a friend at the end of my first trip to Japan. A Distant Neighborhood by Jirō Taniguchi meets me again in Japan, seven years later.

I explain to the couple how I discovered this manga, I show the photo of the French cover that is on this blog. The owner grabs the thick book and asks me to follow him. We cross the garden I just walked through, and at the back on the right, there’s a corridor leading to a door; I hadn’t noticed it. It opens onto a raw stone bridge without railings, just wide enough for one person. It spans a small river, water flowing steadily; it forms waterfalls over stones glistening in the sun. We cross, he holds the manga, stands in the middle of the street with it in front of him. I can’t believe my eyes: the street behind him, the wooden houses, the river, the stone bridges—they are exactly the drawing on the cover of Taniguchi’s manga. That drawing I had looked at so many times with emotion is now before me, real.

Journeys are impermanent paths, trajectories through the universe whose stages form a Möbius strip. On this strange shape with only one side, we move forward without realizing the true nature of space and time. Their combination plays tricks on us, deceives us, disturbs our certainties by sometimes letting us glimpse worlds that seem parallel. We endlessly seek what lies behind the scenes, the explanation of reality, but there is nothing. The more we dive into the world’s explanations offered by sacred texts, the more our mind feels belittled. The more we look at the model proposed by science, the more our mind feels overwhelmed. 一期一会, each moment is unique and must be fully lived because it will never happen exactly the same way again. That’s what this expression from the tea ceremony tells us; it perfectly describes the impermanence of Zen Buddhism.

一期一会

Ichigo ichie – one life, one encounter.

I love this country

Mata ne