Ohayou

July 13, 2025

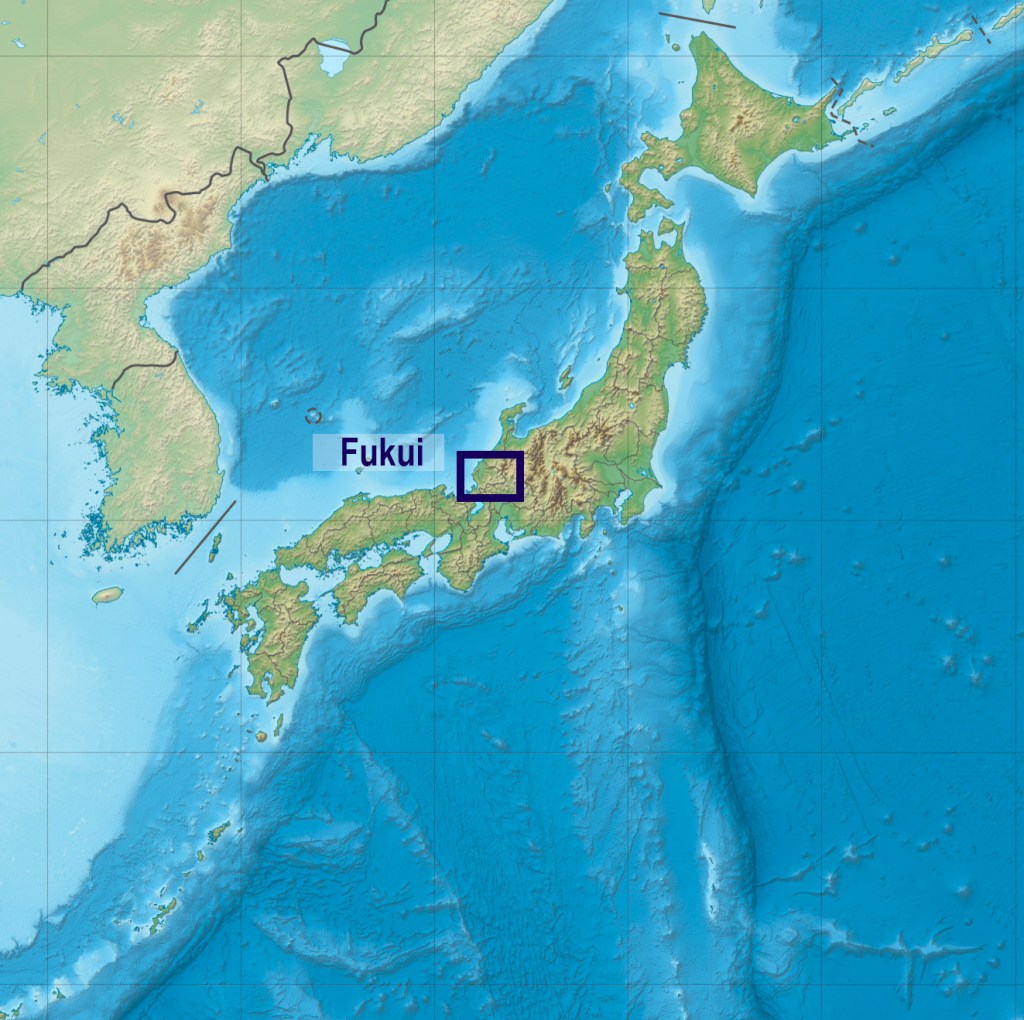

It is never easy to leave a place—barely discovered, just tamed—you have to leave and start again elsewhere. That is the purpose of travel, its impermanence in itself. Leaving Hokkaidō to reach Honshū, the central and largest island of Japan, I pass both under the sea and above the 30-degree mark. The shock is significant when I arrive in Fukui, in the prefecture of the same name, just south of Ishikawa where Kanazawa is located. It’s not the south—we are far from Okinawa’s tropical climate—but at 6:00 p.m. it’s over 30 degrees, and I’m not used to it yet.

Fukui is still a new city in terms of tourism. The shinkansen has only stopped here since last year; it was extended from Kanazawa and now ends in Tsuruga. The high-speed train is a decisive factor in the gradual invasion of Western foreigners into Japanese cities. When I first came to Kanazawa in 2018, the shinkansen had been arriving for three years, and Western tourism was just beginning to emerge. Today, the city is literally overrun—hotels have sprung up like poppies. The paradox is that the hotel supply is so abundant, the competition so intense, that prices are incredibly low for all comfort levels.

Fukui isn’t there yet—not by a long shot—I’ll hardly encounter any Westerners. There are two advantages to this. The selfish and somewhat vain feeling of going where others don’t. More importantly, finding again those smiles, those glances, those gestures of welcome. They had moved me so much on my first trip—they are rarer now. Passersby stop and talk to you, ask where you’re from, thank you for coming to Japan. These are deeply moving moments, pearls of travel, little gifts spoken with disarming sincerity. In Fukui, I find them again on my walks.

Two reasons led me to stop in this city. The first is an old one: the desire to discover Eihei-ji, a Zen Buddhist temple nestled in the mountains, the most important of the Sōtō sect, the most widespread in Japan. The second reason is gastronomy. A Japanese chef recommended Fukui to me as the region where you eat best in Japan. The quality of his cooking convinced me to follow his advice. I must admit I was a bit disappointed—I may not have found the right places. When desire is present, suffering lurks—Buddhism has often told me so. I don’t know how to listen—I keep desiring in vain. Sake consoled me—unquestionably, the best I drank was in Fukui.

Yet it wasn’t the sake that made me see dinosaurs. The region is a major center of Japanese paleontology—to the point that a Fukuiraptor was discovered in the hills of Katsuyama in the 1990s. The museum in Katsuyama is simply one of the world’s largest museums devoted to dinosaurs. In fact, they’re everywhere—in the streets, public buildings, even craft beers bear their names: the Dino King and the Dino Kid from Our Brewing. I watch a little boy, maybe five years old, playing with an interactive ad placed at a bus stop. He touches the legs or tail of a Fukuiraptor four times his size, which growls back aggressively. The boy screams in fear and delight and keeps playing—bolder each time. Further on, I get roared at by a T-rex—impressive.

To reach Eihei-ji, you have to take a local train on the Echizen Railway Katsuyama line—not at the main JR East station, but right next to it. By the time I find it, I just make the train—missed it by thirty seconds. I love local trains—they pass through countryside, rice paddies, villages, stop like subways, and often manga or anime scenes come to mind. It’s 25 minutes of local life for less than three euros—and the countryside is beautiful, far more than the cities.

After 11 stops, you get off at Eiheijiguchi. There, on the platform open to the turquoise sky, silence falls as the train leaves. Only the 蝉 cicadas make the air vibrate with their tymbals, which beat hundreds of times per second. In Japan, these love songs have names. Minminzemi is a continuous metallic sound; Higurashi is more melodious and carries a hint of sadness; Aburazemi is thick and recalls the sizzle of tempura; finally, Tsukutsukubōshi is the song of late summer. And then, the cicada having sung all summer long, found herself quite bereft…

蝉

Semi – cicada.

The song of cicadas is omnipresent in summer in Japan, and sometimes it’s of almost frightening intensity. It rises in a crescendo, as if it will never stop growing. It accompanies me as I search for stop 86, which should take me to the temple. I have a few minutes to find it—my digital guide is playing tricks, it’s very imprecise, and the stops are barely visible. I find it—a minute too late. But it’s my lucky day—number 86 is a few minutes late and takes me where I need to go. Sometimes, the wayward traveler is under a lucky star.

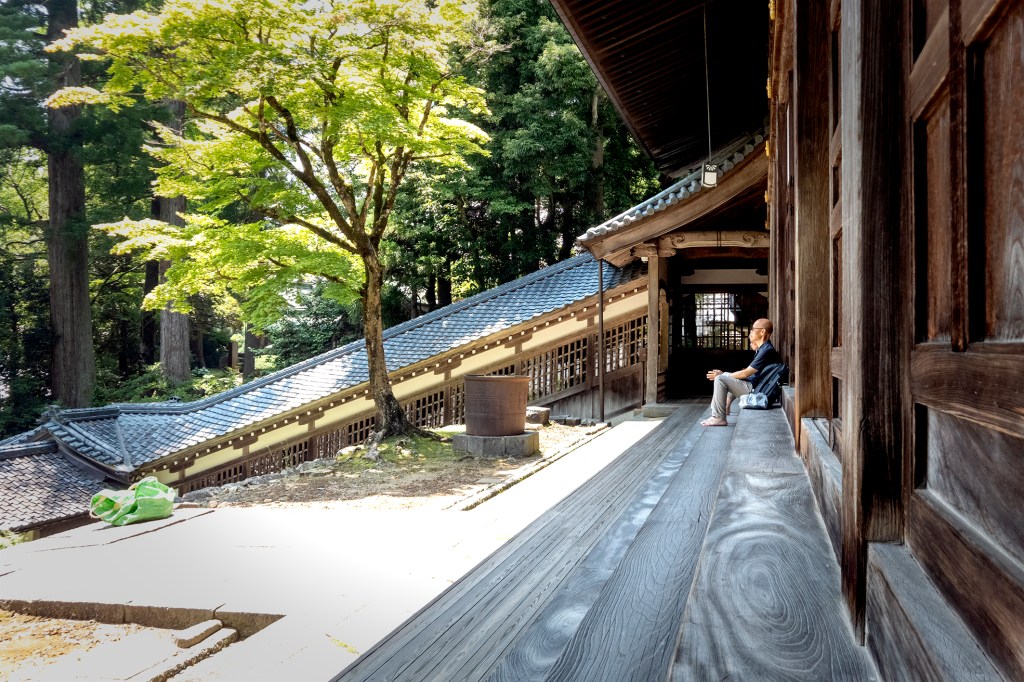

Eihei-ji is an extremely important temple. My friend Hisae told me about it—she visited it last winter under the snow. Zazen is practiced there—the seated meditation of Zen Buddhism. Those who wish to learn it are welcome and are guided by the monks. Hisae emphasized how a very special atmosphere emanates from the temple and the surrounding gardens. One feels touched by something greater. As if all the silent meditations that took place there joined into a single silence to show the harmonious path to awakening.

Eihei-ji was founded in 1244 by Master Dōgen, one of the greatest thinkers of Zen Buddhism. The temple has never been moved since that time, but it has been destroyed several times by fires and the clan wars of the Sengoku period in the 15th and 16th centuries. In 1580, the temple was almost entirely destroyed during regional conflicts. It would be rebuilt in stages over the following two centuries. Most of the current buildings date from the 18th century, all reconstructed following Master Dōgen’s original plan. The reason is clear—from the sky, the major buildings form a seated Buddha in zazen meditation posture.

When I arrive around 11 a.m., it is already very hot—the small uphill walk from the bus stop to the temple entrance is quite steep, and I seek shade, walking slowly. Along the way, I see a group of visitors getting off a bus, chaperoned by a guide waving a flag—Spaniards mixed with some Americans—a curious New World blend. Bad luck in a Zen temple—the regimented group will pass through in tight formation, speaking loudly, barely looking, while the guide delivers a speech at full volume that no one seems to care about. But it’s a day when I am protected by I don’t know what force that ensures my visit will be unforgettable.

The temple is surrounded by thousand-year-old cedars—in this timeless forest, light pierces and reflects in an indescribable way—there’s a velvety green over everything: the stones, the sculptures, the water, even the air. I let the group pass, marching straight ahead under orders, heading without hesitation to the temple entrance without noticing the incredible luminosity that must vary with each day and season. I am lucky to be alone in this unique universe—it can only exist here. The few visitors outside the group do not stop, do not look, do not feel the astonishing freshness—the cedar canopy regulates the heat, conditions the slightly humid air with its leaves and branches. There is an invisible mist, a summer sunlight impression, it transforms reality into green strokes laid by a brush.

At the foot of the stairs leading to the temple entrance, beside the dragons for purifying one’s hands, stands a curious statue. The goddess of compassion, Kannon, carried by a leaf, recalls one of her apparitions to Master Dōgen himself. She came to him during the journey he made to China at 23 years old, seeking an answer to a theological question that haunted him: “If all beings possess the Buddha-nature, why practice?” He discovered in the Caodong school the pure zazen taught by Master Rujing—a meditation without technique, without object, without goal. Just sitting. For him, everything became clear—this demanding practice became the foundation of his Zen: meditation is not the means to awakening—it is awakening itself.

只管打坐

Shikantaza – just sitting.

Eihei-ji includes seven main buildings connected by covered walkways—they form the Buddha in zazen posture. These are surrounded by many other buildings of various uses, including housing the ashes of monks and laypeople connected to Eihei-ji. The seven main buildings are places for zazen practice. The Hattō, the Buddha’s head, where teachings are heard. The Butsuden, where the three Buddha statues—past, present, future—are located: his heart. The Sanmon at the entrance, the gate of the three gates: that of emptiness, that of the formless, and that of non-action. They are there to liberate those who pass through from greed, hatred, and ignorance. There are also much more practical buildings—the bath, the kitchen, the toilets—they too are essential for proper zazen practice.

I find it hard to describe such a place. It is beyond me, beyond my words—I find them frivolous or simply too complex to be accurate. So I stop. I no longer write, no longer think, I stay suspended, emptying my senses and my mind. From the flight of a dragon comes the feeling that air is a subtle movement in tune with light. Two monks pass, greet respectfully, continue on, chatting cheerfully. In the Hattō, a woman alone in zazen seems frozen in space and time. She lifts her head, and I see she is crying—I move away. Harmonious paths are there—they take different forms and rhythms. As Dōgen wrote: “Time is an expression of being—each moment is absolute.”

It is never easy to leave a place—barely discovered, just tamed—you have to leave and start again elsewhere. That is the purpose of travel, its impermanence in itself. I find a small book listing Zen principles. I read: 無常ならざるもの. I can then set off on a harmonious path, leave this place I may never see again. It exists independently of me—I exist independently of it. Encountering it was an absolute moment—leaving it is another.

無常ならざるもの

Mujo nara zaru mono – everything is impermanent.

The sun is harsh—on the way back I walk without thinking. Yet reality forces me to. A delivery man delivers—I pass him—he passes me—stops—delivers again. Houses appear in the Japanese countryside, catch my eye, the camera clicks. Someone is cutting weeds in a rice field with a long-stemmed machine. The noise echoes—grabs my attention—what is he doing—why cut these weeds? In the middle of nowhere, a vending machine with cold drinks surprises me. A kite soars over a rice field, makes a few dizzying dives in the air above me, then flies away. Each moment is absolute—but how to simply accept it without trying to interpret it—without thinking.

I love this country

Mata ne