Ohayou

June 22, 2025

Setting off at random, without any real goal, allows discoveries to unfold free from the burden of predetermined itineraries. Sometimes it takes time, but one must be patient—reward is almost always waiting somewhere along the way. That’s why I try to follow Japan’s harmonious paths, without rushing, without stubbornly chasing after things that must supposedly be seen.

There’s no point looking for temples—they’re there, waiting, and they won’t move, even if impermanence inevitably alters their shape and feel. Harmonious paths aren’t meant to be desired; they are meant to be followed, without knowing where they lead. To desire is to suffer; expecting nothing allows the joy of seeing to surprise.

It was in this spirit that I was surprised, turning a corner, wandering down an alley I had followed by chance, to discover a temple with a name as curious as it was provocative: the Ninja dera. “Dera” is the kanji 寺, the one for Buddhist temples; it’s more commonly seen and said as お寺, with the お as a respectful prefix. It also appears in the temple’s real name, 妙立寺, but this time it’s pronounced “ji”; Japanese is not simple.

寺

Dera – Buddhist temple.お寺

Otera – Buddhist temple (with respectful prefix).妙立寺

Myōryū-ji – Temple of Subtle Elevation.

What draws attention is the word Ninja, which deserves a little linguistic explanation. Japanese kanji have two readings—one purely Japanese, the other Sino-Japanese. (There are often more, but I’ll keep this simple.) The reason is historical: kanji were introduced to Japan by the Chinese in the 5th century CE, alongside Buddhism. The Japanese kept the pronunciation of their own, unwritten language (kun’yomi), while also adopting the Chinese reading of the characters (on’yomi); Japanese is not simple.

The word 忍者 can therefore be read in two ways. Before the 20th century: Shinobi. Nowadays: Ninja. In fact, 忍者 is a sleek contraction of 忍びの物, the original term meaning “person who hides, who acts in the shadows.” That’s exactly the idea of the modern Ninja: clad in black, blessed with supernatural powers, mysteriously and lethally armed, supremely skilled in every martial art. This character was entirely created by cinema—it never existed in that form in Japan. The Shinobis were spies and mercenaries hired by Samurai for their unconventional methods, which the Samurai deemed unworthy of their own code.

忍者

Shinobi, Ninja.忍びの物

Shinobi no mono – person who hides.

So why the name Ninja dera for a temple built in the 16th century, when the word “Ninja” only became popular in Japan after World War II? First, because the myth of the Ninja, crafted by cinema, became as popular in Japan as it did in the West. Second, because this temple is a small marvel of ingenuity designed to deceive the enemy.

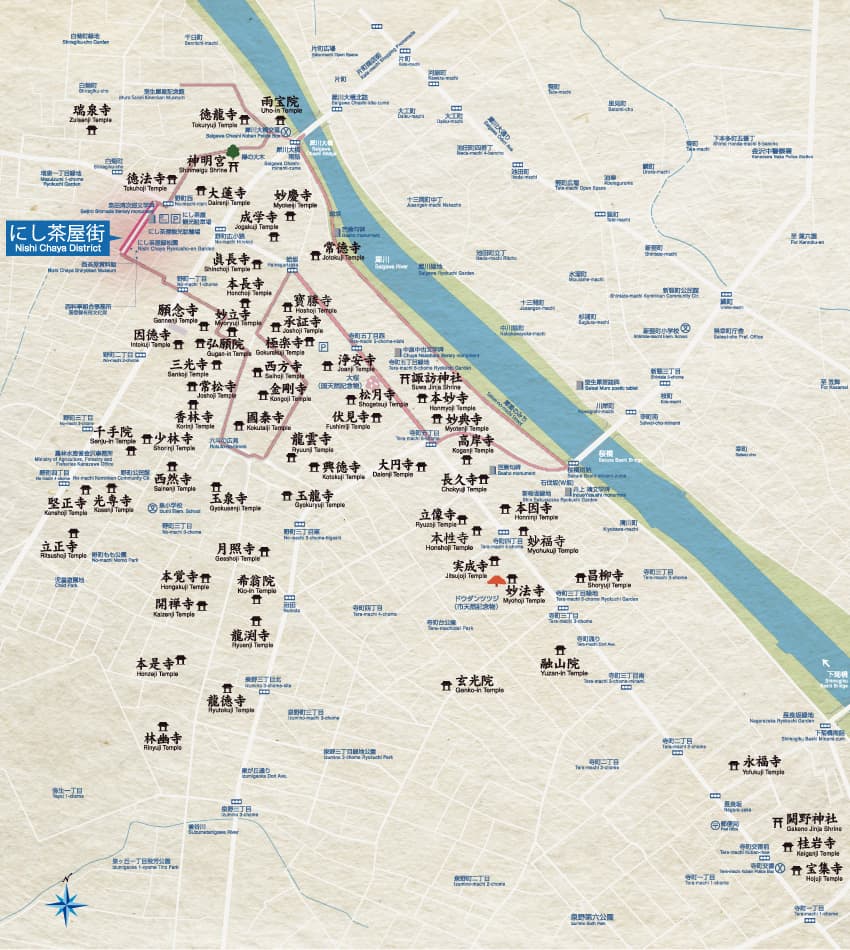

The temple was built in 1585 by the Maeda clan, who ruled over the province of Kaga—today’s Ishikawa Prefecture, of which Kanazawa is the main city. It originally stood near the Kenrokuen Garden and was just a small prayer temple. In 1643, it was relocated to the left bank of the Sai River to reinforce some forty temples moved by the Maeda to form a spiritual and physical line of defense against the Tokugawa shogunate.

Once Japan was unified by Tokugawa Ieyasu in the early 17th century, warfare ceased completely. But the Maeda clan—initially enemies, later allies of the Tokugawa—were the wealthiest of all the feudal lords apart from the Shogun himself, and thus seen as potentially the most dangerous to the new regime. The successive Maeda rulers had the political wisdom never to confront the Shogunate head-on, which allowed them to keep their power and wealth. Yet they remained wary of the Tokugawa. Quietly, they built this defensive line of Buddhist temples around Kanazawa Castle.

A strange strategy? Not really. To secure peace, the Tokugawa had banned the construction of military structures, particularly any buildings taller than three stories. A temple, sturdily built and surrounded by solid walls, remained discreet and could serve as a formidable stronghold if needed. More than forty such temples, aligned strategically along the river at short intervals, could form a genuine fortress—very hard for any enemy to breach.

The Ninja dera is the pinnacle of this defensive tactic in terms of sophistication. It appears to be only two stories tall, small and harmless. In reality, it contains seven levels, 23 rooms, and 29 staircases. It’s a gem of military architecture riddled with traps of every kind, which visitors can explore under the overly cautious and slightly stern guidance of staff who explain everything only in Japanese.

I meet Hisae in front of the Ninja dera on a brilliantly sunny day. It’s hot, but unlike Tōkyō, the wind blows in Kanazawa. So even when temperatures rise above 30°C, they remain bearable—unless humidity gets heavy, which isn’t the case today.

You have to reserve to take the tour—Hisae had taken care of it. She was very surprised that I had never visited the Ninja dera, given how many times I’ve come to Kanazawa. It’s hard for her to grasp my way of wandering aimlessly. In Japan, everything is precisely organized and planned—there’s no room for randomness in a visit or a trip. And precision isn’t limited to travel; it’s also a matter of respect for rules.

In Japan, things often begin with the rules of the place you’re entering. As soon as we step inside the Ninja dera, I receive a laminated document listing all the rules to follow within the temple, translated for visitors. Given how packed it is with traps, pitfalls, false doors, and hidden staircases, it makes sense. But I’ve had the same experience in a cat café in Tōkyō—I think the list there was even longer.

We visit the temple with a guide who gives explanations only in Japanese, while foreign visitors are handed a detailed booklet translated into several languages. So we follow along by reading. The space is very cramped, especially for tall people, and at each new room, our guide insists on carefully positioning us—some standing, others sitting—so everyone can see what she’s describing.

Forty minutes of a fascinating tour—discovering architecture built to slow and destroy any invader. A guerrilla masterpiece devised by a devious mind bent on wounding and demoralizing enemies with spine-chilling ingenuity. One almost hears the screams of pain and terror, the bones snapping, the falls, the cries for help.

As we move through this space, we quickly become disoriented—we revisit the same rooms through hidden doors or concealed staircases. It’s impossible to tell how high up or where we are. The ceilings are especially low, making katana use nearly impossible for any invading Samurai, while defenders wielding spears, pikes, or throwing weapons could do serious damage.

One room catches our attention. It’s small and sits lower than the one next to it. It has two peculiarities. Once you enter and the door closes, you cannot leave without help. Also, it’s made of four tatami mats—something never done in Japanese homes. The kanji for four, 四 (shi), is pronounced the same as the kanji for death, 死 (shi); Japan is a superstitious place. This room is indeed the death room—meant for a defeated Samurai to perform 切腹, ritual suicide, also known as 腹切り, literally “belly cutting.” Note that the two kanji are reversed depending on reading: kun’yomi (Japanese – hara kiri) or on’yomi (Chinese – seppuku).

四

Shi – four.死

Shi – death.切腹

Seppuku – open belly.腹切り

Hara kiri – belly cutting.

But none of this ever happened. The temple was never attacked. There were no deaths or injuries. The Maeda clan showed great political intelligence, and the Shogun’s clan, the Tokugawa, never felt the need to strike this potential enemy. Peace lasted over two hundred years. When the last Tokugawa Shogun fell in the mid-19th century, the Maeda submitted to the victorious Emperor, once again showing intelligence and political wisdom.

During all that time, the Maeda expressed their power not through arms, but through art. They financed local craftsmanship, gardens, beautiful buildings, calligraphy, and music. The age of war was over—a new era began in Japan: the Edo period, named after the old name of Tōkyō. Kanazawa remains one of its most beautiful jewels.

The Ninja dera gave Hisae and me a taste for temples, so we set off in search of a few more in what’s known as Teramachi, the temple district. There’s hardly anyone in the streets. The weather is magnificent, and we wander harmoniously among the temples, now surrounded by modern buildings. A kindergarten has turned one temple’s garden into a playground where Anpanman—with his big red nose and orange cheeks—presides, the most beloved anime character among young children in Japan.

We head toward the castle. It’s been a hot day, and it’s time to go drink a craft beer at DiveFuta’s near the 21st Century Museum. We leave the temples via a very narrow side street that leads to a staircase descending toward the Sai River and Sakura Bridge. These are the alleys I love most in Japan—they remind me of films and offer a moment’s shelter from noise and fury.

Hisae tells me she loves these alleys as much as I do. As we descend the steps toward the river, she starts inspecting the edge of the staircase and shows me her work: the lighting she had installed there, now covered with dead leaves that block the light from spreading properly. She starts clearing it, but with at least fifty steps, it would take her hours to do it by hand. I suggest she take a photo and report it to the city authorities she works with.

Crossing the Sai River, I think back to the Kenrokuen Garden I walked through the day before. It was almost empty, and the late afternoon light—slightly more golden, slightly warmer—gave it a particular languor that kept me there until they announced the gates were closing.

That was a last visit to Kenrokuen, a last visit to the temples for a few weeks. Tomorrow, I’ll head north alone, toward Hokkaidō, to see my friends in Otaru, who are a bit jealous of my love for Kanazawa. I’m leaving the one I love—such is the nature of impermanence—to return to those who welcomed me so kindly in the north a few years ago. We still have the evening and night to enjoy, and they’re always a bit wild in Kanazawa. The air is soft and tender, the sake is cold and joyful. And in the city, Hisae’s lights highlight its beauty.

I love this country

Mata ne