Ohayou

June 10 2025

The rain arrived during the night, and the streets are covered with a film of water that appears uniform. There aren’t really any puddles, but shifting lights reflect to the rhythm of walking and the swaying of the now indispensable umbrella. The 梅雨 has arrived, 14 days earlier than last year, and will last until mid-July.

梅雨

Tsuyu – rainy season.

The rain heralds the arrival of summer. Even if the temperature has dropped a little, the humidity will soon saturate the air, and the heat will continue to rise steadily, becoming harder to bear. It’s not like the monsoon found elsewhere in Asia; this is a climate unique to Japan, which experiences two other shorter rainy periods, one in spring, the other in early autumn. The tsuyu is the worst season for tourism — perhaps an opportunity to seize.

It’s not raining heavily at the moment, nor continuously, but the intensity of the tsuyu varies and can sometimes turn into a real downpour, carrying away everything in its path — land, houses, living beings. The Japanese know this and are always prepared; from childhood, they learn to understand the dangerous rages of nature in their country.

It’s the perfect occasion to return to the 木佐店 I discovered in my new neighborhood of Meguro, a fifteen-minute walk from my room. Dun Aroma is perfect: a long wooden bar separates the customers from the two masters of the place, who prepare tea and coffee with an artistry worthy of a film. They roast coffees from around the world themselves, with names written in Japanese and Roman letters: Peru Chanchamayo, Tanzania KIBO, Golden Mandelin, Yunnan Province China SIMON, etc. This last one is the one I choose, for no particular reason.

木佐店

Kissaten – tea and coffee house.

The coffee is served in beautiful china that has nothing Japanese about it, displayed on the shelves facing where we sit. The ground coffee is placed in a filter on a metal stand about fifteen centimeters above the cup. Hot water, brought to the ideal temperature, is poured in small steady streams from the long spout of a metal kettle. I count the time — it takes over 15 minutes for a cup to be ready to serve.

While savoring the coffee — how could one not, when it’s prepared with such passion — one listens to the soft conversations of the customers, the discreet music, and watches the fascinating ballet of the two coffee masters, who repeat the same gestures with precision, characteristic of Japanese craftsmanship. However, this should not be mistaken for some ancestral practice from Japan’s much fantasized historical past. On the contrary, it is very modern — coffee only appeared at the beginning of the 20th century, imported by Westerners. What is unique, incomparable, is the method, the meticulousness, the time taken to realize the idea of perfect coffee.

The sound of the beans dropping into the machine’s container and the precise grinding are the loudest noises heard in this place where time has neither stopped nor been lost, as the cliché goes, but instead seems suspended in a kind of cocoon made of the aromas of freshly ground beans patiently and skillfully infused with hot water. A madeleine might add a bit more of that cocoon, but is it really necessary?

I leave the magic of coffee to return to Tōkyō, which I no longer like so much. Too many people, too much business, too many cars, too many bicycles, too much noise. The city is fascinating when one discovers or rediscovers it, but after a few days one tires of the constant crowds, whether in the famous places sought out by visitors or in the subways that always seem full except at dawn and during brief lulls throughout the day. Everything moves all the time in Tōkyō, an impermanent city.

One must therefore regain the desire to walk in this endless city, to set out to discover an unfamiliar neighborhood — but for that, one needs a reason, a goal. Robert Guillain’s book Les Geishas, whose story mainly takes place in a few neighborhoods of Tōkyō that were once home to geishas, near the tea houses or restaurants where they practiced their artistic talents.

Before and after the war, there were mainly three such neighborhoods: Akasaka, which I know and where nothing remains of that era, Shinbashi, and Kagurazaka, where I am going today. It’s lively, and a few alleys still remain, evoking a past that is slowly disappearing — but such is the nature of things, the nature of impermanence. The neighborhood is quite pleasant around the alleys of Hyogo Yokocho and Kakurenbo Yokocho, with many izakayas, all kinds of bars, and very few tourists.

I pass an elderly woman wearing a magnificent kimono. She slips into a wooden-looking house in a narrow alley; for a very brief moment, there’s the illusion of seeing the world of the past, that of Guillain. At the end of this small street, where it widens, a huge black limousine is parked, surrounded by a fairly large group of Japanese people of all ages. An elderly man, visibly important, is helped out of the car by an assistant or secretary. Everyone bows respectfully.

It’s time to meet Takashi, time to go eat at one of those izakayas he has a gift for discovering, places I probably wouldn’t be able to enter without him. It takes a little over half an hour by subway to reach Musashi-Koyama and walk to Tsunagiya, where my friend is waiting. A few small tables and a counter behind which the chef prepares yakitoris and sashimis.

When one leaves Japan for several months, one forgets how good the food is. And even though there are some quality Japanese restaurants in Europe, they never quite match the quality of the products found in Japan, nor their variety, and even less so their price. For superior quality, the price is three or four times lower in Tōkyō, and the difference is even greater outside the capital — provided, of course, one doesn’t fall into the tourist traps.

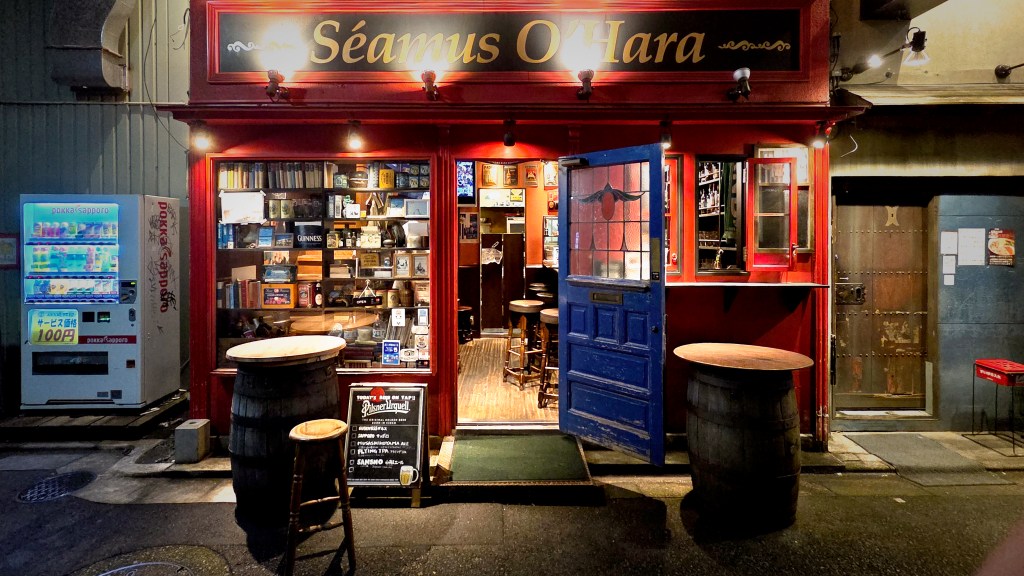

That’s what the owner of Séamus O’Hara explains to us — an Irish bar in Tōkyō that Takashi and I discover by chance. Guinness on tap and a decor worthy of other similar bars I frequent in Europe. He tells us about prices soaring in certain places because of tourists: 3000 yen for a ramen — 18 euros — a ridiculous price that only tourists pay; the normal price of a ramen generally ranges from 850 to 1200 yen. Tourism is surely good business for some, but for many Japanese, it’s a difficult issue to accept.