Ohayou

December 2022

Makki is waiting for me in Otaru, I told her my arrival date and she knows that I will come to dinner at her place on the first night. We have not seen each other for three and a half years, and during this long interruption of my relationship with Japan we have spoken very little through messages. New Year’s greetings, some news of both, but nothing more. The Japanese have these two great qualities, they respect the private bubble of others and they do not forget anything, they have an amazing memory.

When I arrive in the Izakaya of Makki, the first thing she does after inviting me to sit down is to release a large album that contains photos. She hasn’t forgotten anything I told her three years ago, even if we don’t speak the same language, she knows that I love Japanese cinema.

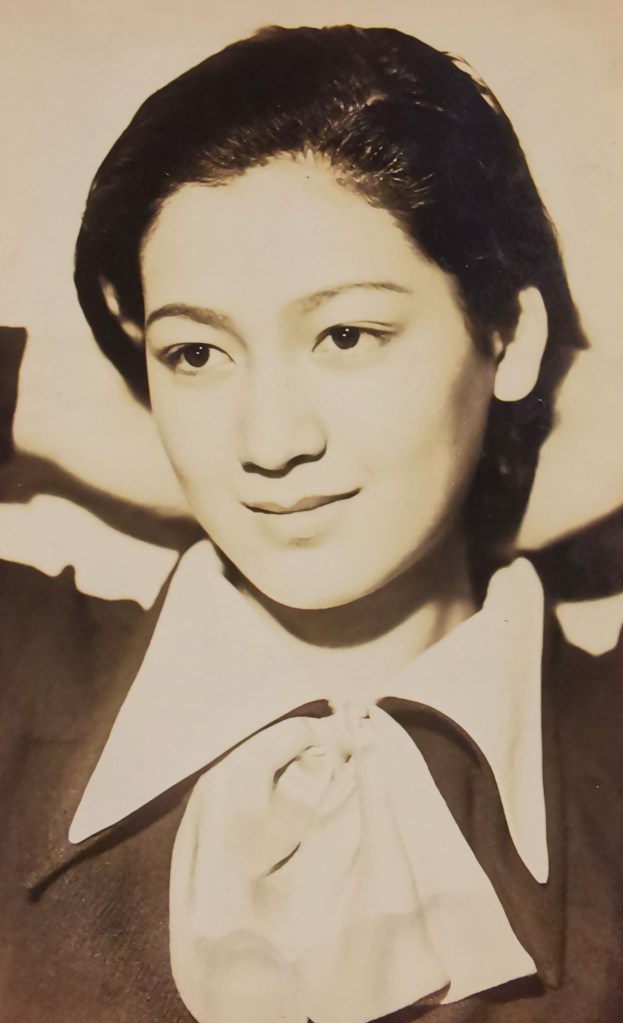

The album that Makki hands me contains photos, old pictures of actors and actresses from Japanese cinema. The first one she shows me is a portrait of Setsuko Hara, the fetish actress of Yasujirō Ōzu, extraordinary character from Tokyo Trip which I consider to be the greatest film in the history of cinema. Gilles Deleuze said of Ōzu: “He managed to make time and thought visible and audible”.

Setsuko Hara was a star before Ōzu made her play in his films. She was a bit like these Japanese actresses of today who are pop stars a little superficial but not necessarily without talent, quite the contrary. She was an icon of Japanese cinema before and after the Second World War and has appeared in over 110 films. But Ōzu will completely transform it and give it a new and unique dimension.

Setsuko Hara is the heroine of six post-war films by Ōzu: Late Spring (1949), Early Summer (1951), Tokyo Story (1953), Tokyo Twilight (1957), Late Autumn (1960), and The End of Summer (1961). The exact relationship between the director and the actress remains a mystery to this day. It is easy to imagine the young woman’s fascination with this extraordinary filmmaker, who was 17 years her senior. But it is too simplistic to assume that there was a mundane love affair between them, a relationship of lover to lover.

In this regard, in the realm of romantic relationships, the Japanese are very different from us in many ways. I won’t pretend to be a pseudo-psychologist, but through Japanese cinema and my Japanese readings, whether fiction or essays, I quickly understood that the codes of Western romantic relationships cannot be transposed as they are to Japan.

Setsuko Hara and Yasujirō Ōzu undoubtedly shared a mutual fascination; this is certain and becomes evident when watching the films in which she appears. But no one knows if this fascination ever became something more, what we would call a love story.

What we do know for certain is that when Ōzu passed away on December 12, 1963, his 60th birthday, Setsuko Hara announced a few days later that she was ending her career. She was 43 years old. She never acted again, never gave an interview until her own death in 2015. For 52 years, she remained silent publicly and never spoke about her relationship with Ōzu.

Setsuko Hara spent the last 52 years of her life in Kamakura, near Tokyo. Ōzu shot many of his films in Kamakura; he also lived there and passed away there. The filmmaker was buried in Kamakura, and throughout all the years she lived there, Setsuko Hara regularly visited Ōzu’s grave. Local residents occasionally caught glimpses of her discreet silhouette on the path to the temple.

Makki, three and a half years after my last visit, hasn’t forgotten that Setsuko Hara is the actress who moves me the most. She searched through her grandmother’s album, which contained a collection of Japanese cinema photos, to find a picture of her, which she offers to me.

On one of the photos I attach to this column, there is simply the cover of the album with a name, Makino, written by hand in romaji, the name that the Japanese give to the Latin writing. The layout is a bit awkward, at that time it was probably rare to write a name other than in Kanji. This name, Makino, is the family name of Makki written not his grandmother. My friend’s real name is Yuka, but everyone calls her Makki.