via Wikimedia Commons

Ohayou

January 2023

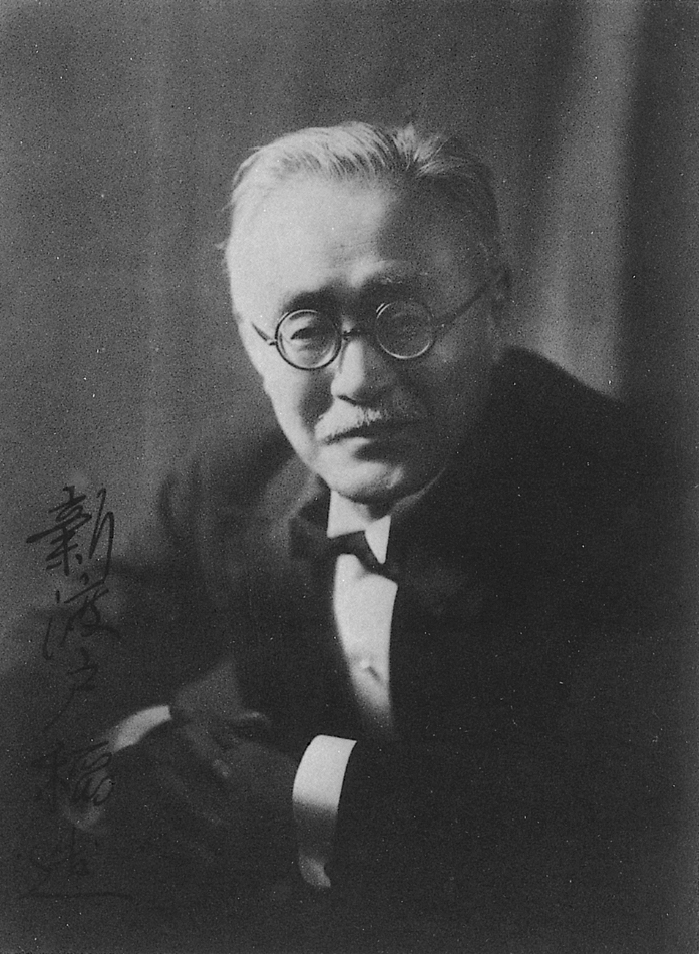

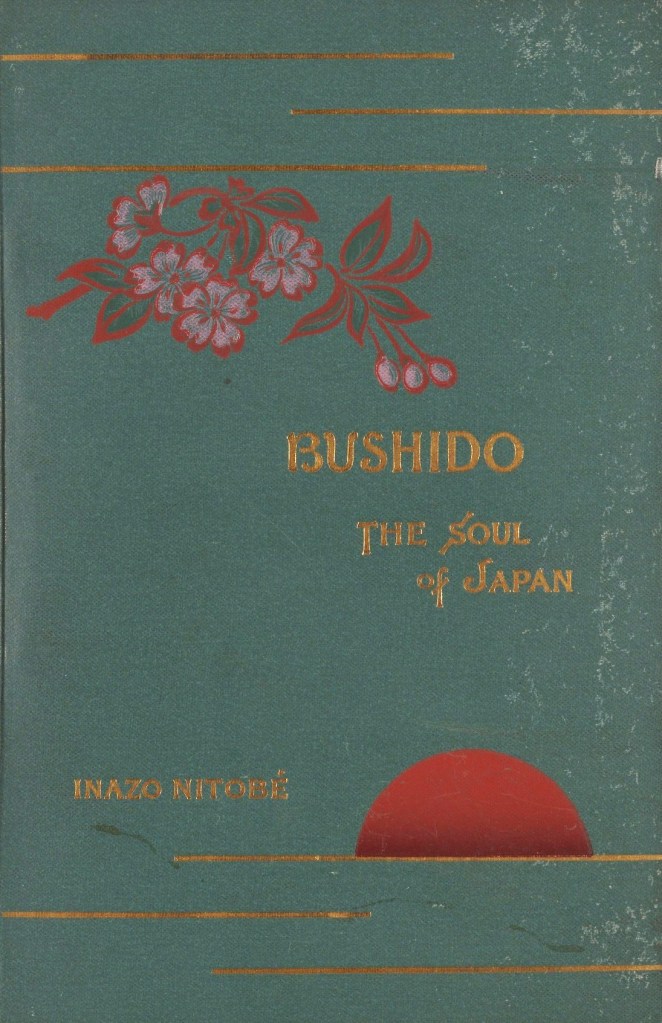

武 士 道 was written in 1899 in English, in the United States, by Nitobe Inazō, a doctor of agronomy and law, and university professor.

武士道

Bushidō – the way of the warrior

His book, which was not translated into Japanese until 1908, is primarily aimed at introducing Americans to Japanese culture. He is thus reinventing a past of bravery and dignity that is not at all the reflection of what samurai were before the Edo period. Before the 17th century, warriors were cruel, extremely violent and often had only their own or their clan’s interests as their way of life and certainly not a way based on moral principles that would be given to the samurai of that time much later, at the beginning of the 20th century.

Later, during the Edo period, the samurai were transformed by the Tokugawa shogunate into a new military nobility at the top of the social hierarchy. A nobility administering its fiefs but not working, a nobility of literate trained through neo-Confucian education. Fierce warriors become powerful, elegant and refined aesthetes, totally subject to the hierarchy of Tokugawa power whose greatness they embody.

Nitobe Inazō, who converted to Protestantism at a young age and became a Quaker in the United States, describes in his book a perfect Japan and courageous samurai, defenders of the weak, always faithful and respectful of a very strict code of honor, the Bushidō. He paints an ideal portrait of his country and culture, adding a very Christian colour. Its intention is to prove to the western world that there was a noble chivalry in Japan, like that of Europe, and that consequently his country deserves to be among the great of this world. He writes: “The light of Japanese chivalry, the orphan daughter of a dead feudalism, still illuminates the paths of our morality”.

The book Bushidō would not appeal much to the military dictatorship that seized power in Japan in the early 1930s—it was too Western, too Christian. Nitobe Inazō even faced some trouble at the end of his life. He envisioned a Japan open to the world; he was a pacifist who had worked for the League of Nations, the precursor to the United Nations. Meanwhile, the Japanese far-right dreamed of an all-powerful Japan dominating the world, which would ultimately lead to the disaster of World War II.

Nonetheless, Nitobe’s book is still interesting to read, provided one does not take it as a historical account but rather as a well-intentioned piece of gentle propaganda. It is still read in Japan today in its 1938 translation. A Japanese friend recommended it to me to better understand the Japanese mentality.

She is not wrong, but I think she places too much trust in the mythical past idealized by Nitobe. She does not share my reservations about the content and its distinctly Christian influence. However, it remains true that one can learn quite a bit about Japanese ways of thinking by reading Bushidō.

This book is not very well known in the West today, but it remains popular in Japan because it offers a vision of duty and morality that aligns with modern postwar Japan.

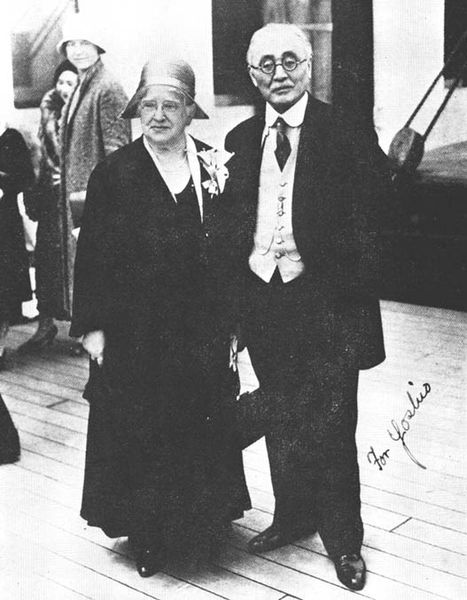

In fact, it is a text of reconciliation between Western and Japanese thought. Nitobe Inazō was born in 1862 into a samurai family. He followed samurai training until the status was abolished in 1867 during the Meiji Restoration; he was only five years old at the time. He was brilliant, and by the age of 15, he was studying at Hokkaidō Agricultural School, where he met W.S. Clark, who converted him to Christianity. He learned English, went on to study in Tokyo, and then in Germany. Later, he traveled to Baltimore to study political science. He became a Quaker and married the daughter of a highly influential Quaker in the United States. He returned to Japan with his wife to become a university professor.

Inazō Nitobe was fascinated by Western culture, which he discovered during his time in Germany and the United States. He wanted to bridge the gap with Japan’s ancient culture, which was already beginning to change under Western influence. This is why he wrote Bushidō, intending to spark the interest of Western elites in Japan—a nation that was just beginning to emerge after more than 250 years of isolation during the Edo period.

Above all, his goal was to present Japanese culture to the West, and Nitobe Inazō spent his life striving to be the bridge between the two worlds. In 1920, he became the Under-Secretary-General of the newly created League of Nations, though Japan would leave the League in 1933 following its invasion of Manchuria in 1931. This was a symbolic failure for Nitobe, who was no longer a diplomat at the time. Ill and disillusioned, he died in Canada in October 1933, likely realizing that Japan was heading toward disaster.

Nitobe Inazō’s Bushidō is also an attempt to sacralize traditional Japanese values in a Christian manner. While many of these values were largely invented, they resonate deeply with the Japanese psyche. This is evident in the fact that they are still referenced today in certain social and professional interactions.

Nevertheless, I will leave the conclusion on Nitobe Inazō’s Bushidō to historian Shin’ichi Saeki, a scholar of medieval Japan who teaches at Aoyama Gakuin University.

“Nitobe conceives Bushidō as a moral code ready to be applied as it is to modern society—very different from medieval Bushidō. Through this book, he transforms Bushidō into a perfect moral system.

However, we must pay attention to the circumstances in which this essay was produced. Nitobe wrote it while resting in Monterey, California, where he was staying for medical treatment. It seems that after meditating in accordance with Quaker practices, he dictated the book in one go without conducting extensive research. Nitobe had no knowledge of the historical development of the concept of Bushidō.

He used the term but essentially crafted his own interpretation of it. It was only thirty years after publishing the book that he discovered the word Bushidō in old texts. Unfamiliar with the history of medieval Japan, he had no historical ambitions. Instead, he relied on his individual experiences and particular sensitivity to discuss Japanese culture in comparison to Western culture. The Bushidō he describes is therefore a pure creation without any historical foundation.

Yet this book, written in plain English, was highly appreciated in the West. It was precisely because of its success abroad that it was reintroduced to Japan. While its narrative differed from that of nationalist rhetoric on Bushidō, in some ways it aligned with nationalist discourse, as it enhanced the prestige of Bushidō and contributed to the prevailing trend of reviving the Way of the Warrior.”

Bibliography

- Nitobe, Inazō. Bushidō. Le code du samouraï. L’âme du Japon. Paris : Synchronique Editions, 2019.

- Souyri, Pierre-François. Les guerriers dans la rizière. La grande épopée des Samouraïs. Paris : Flammarion, 2017.

- Shin’ichi Saeki, Figures du samouraï dans l’histoire japonaise. Revue Annale. Paris : Ecole des hautes études en sciences sociales, 2008/4.